The director and his VFX Supervisor, Jay Cooper, explain how they completely reversed the standard production process for his sci-fi epic, employing spontaneous live-action shoots that looked cool, not controlled, with 3D environments, digital matte paintings, and many other elements on the 1,600 visual effects shots designed afterwards, not before.

There is no doubt that the experience of working as a visual effects artist has greatly impacted how Gareth Edwards approaches digital augmentation in his movies, best exemplified by the filmmaking methodology he employed on his sci-fi epic The Creator. “For the longest time it felt like I had spent 10 years putting off making films, but I actually realized it was like the Karate Kid wax on, wax off filmmaking,” the director shares. “When you’re trying to compose with a camera, if it’s not good, you can move the camera and that takes like two seconds. But if you do that in 3D, it’s such a painful way to learn what’s right and wrong about lighting and composition. Those lessons stick with you. When I got hold of the camera to make my first film Monsters, it was so liberating. I joked that the camera should have a little thing on it saying ‘real-time rendering’ because no matter how fast I moved, I could get a brand new shot. All that pain of doing visual effects was suddenly paying off in filmmaking because you can look at images and know what’s wrong with them and what you would do to make them better. And that’s true of standing next to the camera just as much as it is sitting in front of a monitor.”

Rather than trying to reshape the film’s 80 different locations to match the concept art, Edwards reverse-engineered the process. “The real world has so much random chaos and details in it that I’m sure there will be people watching this film thinking we were clever for adding that little crazy thing,” he explains. “The truth would probably be that we didn’t add it all. That was a guy who just went past while we were filming, and we left it in. There are a lot of elements in The Creator that we didn’t have any control over on purpose.” Digital matte paintings or 3D environments were not designed until the footage was actually captured. “For instance, there is a shot where a missile comes down and there are these teapot-shaped mega temples,” Edwards notes. “A real temple was in the foreground, which had these distinctive roofs. We would copy that exactly and make it in the background as if it were a mile big and then start messing around with the image making it sci-fi, because then your brain can’t tell what was there and what was added. Whenever it looked obvious what we added, we would then start to add other things and change the foreground. We would make the background look like the foreground and the foreground more like the background, so you were never sure where it began and ended.”

Storyboards were created for big set pieces, mainly for reassuring producers that the shots could work, that it wasn’t a “big deal.” “’It’s John David Washington and this other thing,’” Edwards would tell them. “’We’ll do the rest in post.’ It was more so that people could believe that it was possible because it read as crazy ambitious.”

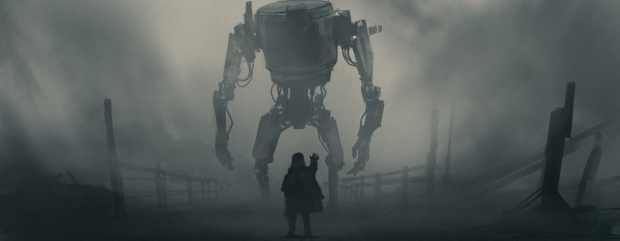

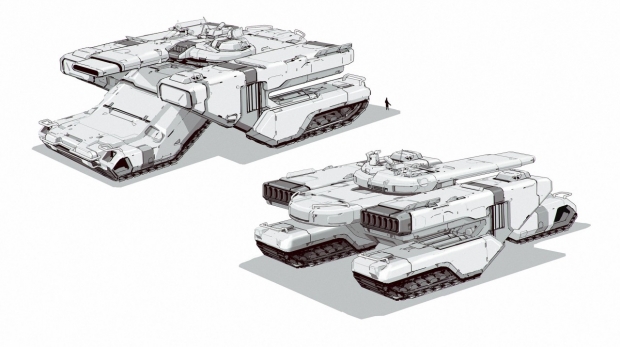

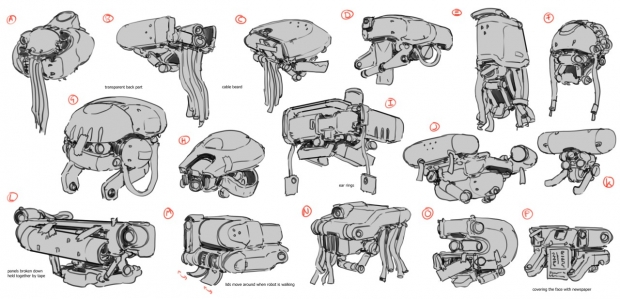

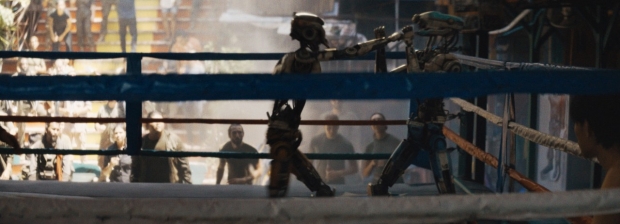

Edwards also shares that the visual design language was driven more by what looked cool than logical. “Let’s put it this way. If you had two designers and put them in different rooms for a day and one of them was thinking of reasons and clever ideas for why things would be the way that they are, and in the other room is a person purely looking at shapes and interesting visual designs, I have more faith that they’re going to come up with something where you then reverse engineer the logic into it. If it feels right then your mind starts to race and go, ‘I bet that is because of this or that reason.’ I wanted the film to be full of things that we couldn’t explain. If you really went into a time machine and shot a movie in 2070 and brought it back, I would have spent a lot of my time with the producers watching the footage going, ‘What is that building? Who is that person? What is that vehicle?’ And I would go, ‘I don’t know. I have no idea. I didn’t have time to ask them. We then had to go and shoot this scene.’ Just like when you go to a foreign country, there are lots of little things that happen where you go, ‘What are they doing? What is that thing?’ It never gets explained to you. You have to move on. We have loads of crazy architecture and strange things that we throw away; that’s what makes Star Wars great in my opinion. Two big legs will go through the frame and never be mentioned ever again.”

The visual effects team, consisting of ILM, MARZ, Atomic Arts, Folks VFX, Fin Design + Effects, Outpost VFX, and Crafty Apes, collectively worked to create a seamless marriage between practical and digital for all 1,600 shots. “We’re in a weird time right now where CG is getting a lot of bashing in the press,” notes Jay Cooper, VFX Supervisor. “It’s not a fair criticism of what is being pulled apart because the reality is if you don’t like the CG in the shot, what you’re really saying is you don’t like the production design and framing. There are a million different places where the CG is one component of what is being created and what we’re seeing now is a knee-jerk reaction to the artifice and the thing that is the easiest to hate is CG. Sometimes those criticisms are appropriate.”

One interesting twist in the film’s creative process was that Edwards was his own camera operator. “It made it complicated on a number of fronts,” Cooper continues. “In the shoots I’ve worked on in the past, either you’re working with a storyboard or a piece of previs and that shot is generically, ‘This is the starting point and from here to there are your marks.’ In Gareth’s approach to filmmaking, if that’s the starting point, then almost for a longer session he’s trying to find more interesting compositions and he’s playing with some of the staging as well as the performance in real-time. In terms of what that means for visual effects, part of the shot you wouldn’t expect to see is now part of the shot, or there are characters present that you didn’t expect. Those things are more freewheeling.”

Lens aberrations were mimicked in CG. According to Cooper, “The primary lens for principal photography was a Kowa Cine Prominar 75mm and a tremendous amount of footage was shot with that, probably greater than 70 percent. There was also the camera itself, a prosumer Sony FX3 camera that has its own range and look to it as well its own characteristic noise. Those are the things that we model and make sure are present in all the shots that we do. That carried onto all CG shots as well. We would apply a virtual lens aberration, grain, and vignette, all those sorts of things, because it was extremely important to Gareth and for me that the look was consistent regardless of what the shot was across the entire movie. We tried to stay as close to using that same focal length. We played with a little bit for composition. Our first hope was that we would keep that focal length as a starting point.”

Atmosphere was incorporated into every shot to add life to the image as well as assist in conveying the proper size and scale. “There is a shot that shows the aftermath of the explosion from a nuclear event that went off in Los Angeles,” Cooper says. “The movie opens with Joshua at ground zero pulling robots out of the debris and exterminating them or putting them in a grinder for extermination. We did the same sort of thing that we did for the rest of our movie, where we’re starting with a plate and trying to figure out which parts to keep and remove, and building the world around the plate in such a way that we can sell the enormity of the devastation. We built a big wall that surrounds the ground zero area and put in all these broken buildings and things. The goal in each of these one-off shots is to tell the story with the maximum impact you can.”

AI/human hybrid characters are portrayed by and Madeleine Yuna Voyles and Ken Watanabe. “There are absolutely huge portions of these actors where we are either reprojecting what was originally there or are blending our CG version of our character in with the photographic version,” reveals Cooper. “They’re hybrids. Every time we’re doing a Simulant shot, we’re using portions of our renders or plates, and reprojecting parts of the plate to try to get it all to sit together.”

The principal cast was cyber scanned in London courtesy of Clear Angle. “We gathered textures in that moment and did an equivalent of a facial shoot” Cooper reveals. “We had facial scans and things like that. Everything else was lighting, compositing, layout and ‘matchamation’ work where we had to match the shape of what Alphie’s [Madeleine Yuna Voyles] existing outfit was or replace elements of it, recreate the background that she was including and using the visual cues that were in the plate if we didn’t have a HDRI or lighting reference.”

Asked whether Rogue One: A Star Wars Story served as a great training ground for The Creator, Edwards is not so sure. “I don’t know how you ever call Star Wars training. It’s the Super Bowl, isn’t it!? Coming out of your own Star Wars, you get excited about what is possible. I still feel the same way now, at the end of this movie. I’m even more excited about the next one because every single time you feel like you’ve learned a lot. You’re like a gambler who goes back to the casino because this time you’re going to get the jackpot; that’s what keeps you going.”