No one talks as passionately about stylized water, and the artists who create it, as Laika VFX supervisor Steve Emerson.

If you’ve ever heard visual effects supervisor Steve Emerson talk about his job, or his most recent work on Kubo and the Two Strings, you’ve probably said to yourself, “Jeez, I so want to work at Laika.” Now, whether you’d want to ply your trade as a CG animator or arc welder is beside the point – Laika’s hands-on filmmaking philosophy, nuts and bolts production mindset and dedication to cutting edge hand-made movies is highly intoxicating. And no one embodies that “we’re kind of nuts” mentality more fully, nor better articulates its coolness, than Mr. Emerson.

We’ve met up many times over the last decade, each time discussing the studio’s increasingly sophisticated and expansive integration of stop-motion animation, rapid 3D prototyping replacement part production and CG-driven digital effects. Two weeks ago at the Motion Picture Academy VFX Bakeoff, I sat in the second row listening to Emerson, along with Brian McLean, Oliver Jones and Brad Schiff, present the stellar digital effects work on Kubo. Emerson and I also spent most of a week together the latter part of this past October at the VIEW Conference in Turin, Italy, where he spoke quite eloquently to the assembled audience of artists, educators and students about the magic that happens inside Laika’s non-descript Portland-based warehouse digs. And about the elaborate and difficult process of creating vast amounts of different types of stylized water on Kubo. Sitting down to talk with me after his keynote, Emerson spoke even more intimately about the passion and collaborative effort behind Laika’s brand of hybrid stop-motion / CG filmmaking. And all things Laika water.

Dan Sarto: After four films and almost a decade at Laika, your role as a visual effects supervisor continues to evolve and expand. How has Laika’s use of digital technology changed over the course of your time at the studio?

Steve Emerson: Our CEO Travis Knight is a stop-motion animator. He is passionate about stop-motion. I work with and collaborate with some of the most talented people in the world when it comes to creating stop-motion universes. I've been there since the Coraline days. One of the things that I found most enchanting, that I was most excited about on Coraline was the level of creative problem solving used in order to get shots in camera, using physical materials. It took me back to when I was a child, before computers came into the mix, and I’d watch a movie and wonder, "How did they do that? How'd they do that?"

Once computers came along, it felt like a lot of that went away. Because now, when you see something extraordinary in a film, you can easily dismiss it as, "Well, they probably did that on a computer." So it [Coraline] brought back this movie-making magic that I felt had been largely lost for probably 20 years in the film business.

When I became a visual effects supervisor at Laika, one thing that was very important to me was that I didn't want to lose that [feeling]. We were certainly going to be adopting more technology and integrating more computer-generated elements into Laika's films, but we were going to do so in order to enable storytellers.

Stop-motion films, they're so difficult to make. Everything needs to be hand-animated. Our animators, if we're lucky, we're getting six seconds a week out of them. Typically, it's closer to three. In the case of the skeleton monster in Kubo, we were lucky if we would get one second. Beyond that, if you're looking at a film like Kubo that is so enormous in scope, how can you create all these worlds and environments in their entirety, physically, and still be responsible with the budget?

Stop-motion films, they're so difficult to make. Everything needs to be hand-animated. Our animators, if we're lucky, we're getting six seconds a week out of them. Typically, it's closer to three. In the case of the skeleton monster in Kubo, we were lucky if we would get one second. Beyond that, if you're looking at a film like Kubo that is so enormous in scope, how can you create all these worlds and environments in their entirety, physically, and still be responsible with the budget?

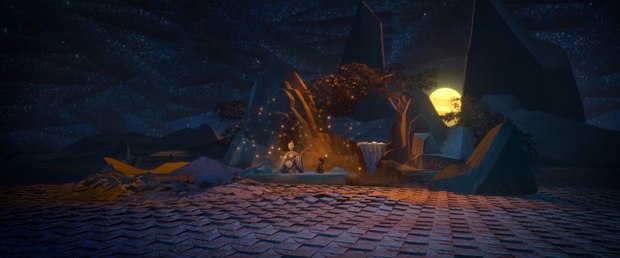

Filmmakers would come in [to Laika] and say, "I want to tell this story." The producer would go through it and it's their job to say, "Okay, we need to simplify this. We need to rethink certain visuals or take certain sequences out because we just can't do all of it in camera." That was really where the idea of creating hybrid films began at Laika. We were going to create these universes and get as much as possible in camera. But when the stages fell short, then it was our job to step in and offer solutions to get whatever visual that filmmaker wanted in order to tell that story.

From ParaNorman to The Boxtrolls and now to Kubo, the responsibility that we've shouldered has certainly gotten larger and larger as the films themselves have gotten larger and larger in scope. But we're still working with essentially the same production budget and a very similar crew that we were back in the days of Coraline.

DS: What were some of the big challenges you faced on Kubo? There's a lot of water in the film. There are big vistas, obviously extended physical sets. What were some of the main areas where we see your work on the film?

SE: The largest challenge we had on Kubo was certainly the water. Water is something that never plays nice with stop-motion animation. We've had instances of water in past films. In Coraline there was a shower that Coraline turned on accidentally and she was sprayed with water. We did all that with 3D replacement animation. We would print up water cycles on a 3D printer and swap them in one frame at a time. We've done a lot of work with water splashes, water running across floors where we'll use different types of materials that you can actually pose. KY Jelly would be one, where you can actually form it and move it and pose it one frame at a time.

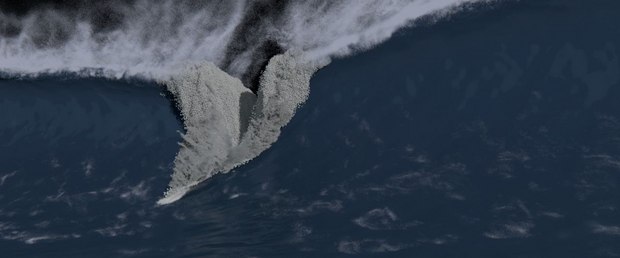

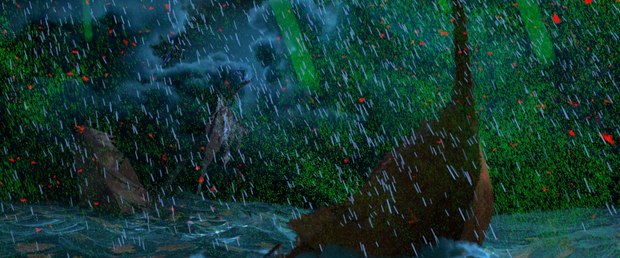

But the thing about Kubo was we were talking about creating oceans, giant waves and lakes along with a lot of character interaction. It was going to be raining. Puppets were going to be jumping off the side of a boat into water systems, swimming through water systems and going underwater. At the onset, it was so overwhelming to look at in terms of tasks, but at the same time, it was really, really exciting! We were going to problem solve something that really, at that level, at that scope, had never been done before.

It doesn't matter if it's an ocean of water, or if it's a background character in a crowd, we make sure that if it's going in the film, it's being built physically first. We make sure that when we build something digital, it's being informed by practical tests and practical materials that are being provided to us by the animation department, by the puppet department and by the set builders at Laika. When we're realizing whatever those items or environments are, we're collaborating very intensely with them [the different departments], prior to anything being shown to the directors.

Now in the case of the water systems, again, we were given very specific artwork and our task at the onset was, "Let's take this piece of artwork and realize it as literally as possible. How are we gonna do that?" Before VFX even gets into the mix, we go out on the stages and put the animation and rigging teams to work. They ended up creating these really amazing water systems using different types of materials, from garbage bags to shower curtains along with this iron mesh that would undulated and roll like an ocean.

Then they would lay various materials over the top of this [the garbage bags and shower curtains] and light things very specifically so we could read different types of patterning on those surfaces. Then we'd watch all those tests together as a team, with the production designer and the director getting into the mix at that point and again, all the other department heads. We watched those tests and said, "That looks amazing. That looks cool. We love that about this." Then we took all the cues and characteristics from those physical tests and created a photorealistic version that formed the base of what would become a water system.

At that point, it's about iterating, adding style, figuring out everything from churn to spray to white caps. For every element that would eventually make up that water system, each had to be designed ultimately to suit the style of the film and feel like they belonged in Kubo's world. Also, for all of those elements, we needed physical reference. So the art department created water churn for us out of paper and showed us what that looked like. We’d take an element like that and again, create another photorealistic interpretation and fold that into our water system until we finally landed on something that felt different, that felt like it belonged in that world, that was exciting and distinctive.

When we finally hit that point for the water system in Kubo and the Two Strings, I think it had been about eight months of development. Then it was a good year before we got into a real groove with all the water work.

DS: Even when you’re employing conventional CG animation tools and techniques, you're integrating them with a filmmaking process no one else is doing, certainly not with the scale and scope of your productions.

DS: Even when you’re employing conventional CG animation tools and techniques, you're integrating them with a filmmaking process no one else is doing, certainly not with the scale and scope of your productions.

SE: Absolutely. There's something about the way that we make films at Laika that is…it's just crazy. It makes absolutely no sense. In the case of Kubo, we built an 18-foot skeleton. Largest stop-motion puppet ever made. We so easily could have done a smaller-scale version, Harryhausen-style. We could have done a CG version. But everybody was so excited by the idea of creating that skeleton that we all jumped in and figured it out. We tend to do things the hard way. It wasn't much of a surprise to me as a supervisor that when we figured out the workflow for creating computer-generated elements to flesh out environments and tell these stories, it would be a complete pain in the neck.

The visual effects at Laika, we never create these elements in a vacuum. And again, it's always informed by physical elements. It's always done through intensive collaboration. It would be so much easier for us to walk away from the stages and jump behind those computers and start creating things that look cool. But we do it the hard way and the payoff for that is we end up with something that feels authentic. But it also feels distinctive. It doesn't feel like anything else that's out there right now in other films.

[Editor's Note: Laika provided an extraordinary set of VFX sequence breakdowns, which we have playing back to back below. Click here for the playlist of individual clips]

DS: Travis has told me that as you grow, you continue to expand your production sophistication and expertise, but there are some stories you can't yet tell because the capabilities of the studio are not quite ready. If you look back over your four films, where you started and where you are now, the differences in your studio are like night and day. And that’s not just because you’re harnessing bigger and better 3D printing systems. Can you summarize how the studio’s overall filmmaking capabilities, the cinematography, the animation and visual effects, have evolved over the course of these four films? How have things changed at Laika over the last decade?

SE: In the Coraline days, when we moved into the warehouse out in Hillsboro, Oregon, where we do all this work, it was just a shell of a building with a big concrete floor. Really, little to nothing else. The thing about Coraline was that we were not only making a film, we were also building a foundation to create movies at Laika. Part of that foundation not only became the physical resources, the sets, the puppets, all of the infrastructure, but on the digital side in visual effects, [it included] a pipeline. The thing about software and pipelines is that they get better and better the more you iterate on them. The more versions you do [build], the more efficient they become and the more they enable you to work faster.

Certainly, we built that infrastructure early on. We created a pipeline that we have continued to iterate on over the course of the last ten years. The best thing about Laika is that the films themselves are films that everybody at the studio is intensely proud of when they're done. The culture there is amazing. People love to work there. It's exciting -- there is a value for work-life balance which is unique in the world of visual effects. I think everybody at the studio realizes that we have something really special. What that means is people don't leave. A lot of the people that worked on Coraline are the same that most recently worked on Kubo.

Over the course of those ten years, from Coraline to ParaNorman to Boxtrolls to Kubo, in creating those films, which got larger and larger in terms of scope and complexity, we made a lot mistakes. But we learned from those mistakes. We became better, more efficient artists. Our pipeline because more efficient and the hardware that backs that pipeline became more powerful.

What it's [the more powerful pipeline] enabled us to do is work much faster and get even better, more dynamic results. It's a pretty amazing thing. These films keep getting larger in scope, but our technology's getting stronger, our pipeline is getting stronger and our artists are getting better, even though each of our films has been made with a very similar budget and production timeline.

DS: What are some of the next hurdles, or challenges, that you’re facing in the continued evolution of the studio? What’s coming next?

SE: I've certainly heard Travis speak to the fact many times that he wants each and every film to be distinct in style. He wants to avoid a studio look or style, though there's a bit of that in every Laika film because they’re all grounded in stop-motion animation. At the same time, in terms of design for all those shows, they are each very, very distinctive. A big challenge is going to be making sure each film feels different from the last. How do we continue to challenge ourselves as we create new and different universes that are really, really unique in the world of animation?

There's been a lot of talk recently about the fact that at Laika, we don’t make sequels. There's been a lot of talk about the fact that we're interested in creating films that have adult protagonists. That isn't something you typically see in animated features. At major studios, there is a strategy for making money. Whether it's using superheroes, using sequels or using talking animals, all of these strategies drive a lot of studio executives in their decision making. I think this [thinking] is completely dismissed by Travis. He is extremely brave in the way he wants to take animation and stop-motion to places where it's never been before, regardless of consequence.

Obviously, we want a blockbuster. We want to move a massive number of people. At the same time, we want to make sure that we're telling unique and engaging stories, or as he says, "We're making movies that really matter." That is ultimately driving the decision making and where we're headed as a studio.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.