Will the VR revolution be stunted by its own myopic evangelists?

The evangelical fervor of tech entrepreneurs is understandable. The belief and willpower required to bootstrap is significant, and the proselytizing necessary to convert investors and consumers is daunting. Among the technorati, Steve Jobs’ famed “Reality Distortion Field” is more often regarded as an admirable attribute than a cautionary quality. But the single-minded drive of unicorn breeders can drift into myopia if left unchecked, resulting in a technology’s champion becoming its worst enemy (*cough* Zuckerberg *cough*). The VR ecosystem is unfortunately not immune to this syndrome.

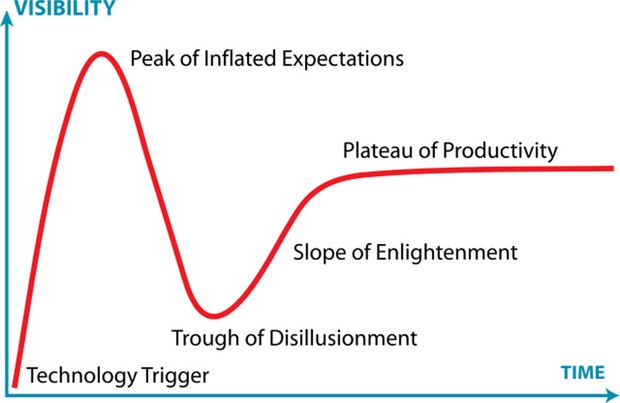

VR will succeed because... the graph

At a 2018 SXSW panel entitled, “How Does VR Become a Truly Mainstream Technology,” VR stalwarts from Baobab Studios, Jaunt VR, Oculus and Fast Company weighed in on VR’s past, present and future. While acknowledging VR’s current challenges, the panelists referenced the Hype Cycle as evidence that salvation lies ahead.

For the uninitiated, the Hype Cycle is a graph developed by the Gartner Research & Advisory Group to represent the maturation, adoption and mass-market application of a given technology. Gartner’s Hype Cycle provides a conceptual mapping of emerging technologies through five (fairly self-explanatory) phases which read like gaming levels: the Technology Trigger, the Peak of Inflated Expectations, the Trough of Disillusionment, the Slope of Enlightenment and the Plateau of Productivity.

I’m bemused when tech evangelists point to the Hype Cycle graph. While the SXSW panelists represent VR’s vanguard, and are diligently doing their part to facilitate the Slope of Enlightenment and attain the Plateau of Productivity, they display a misguided faith in formula. The Hype Cycle is a meaningless graphic that only depicts the successful scenario, not the more probable unsuccessful scenario. The Trough of Disillusionment is not automatically followed by an inflection point into the Slope of Enlightenment. It is more accurately followed by a decision point that could just as easily (and statistically more probably) lead to the Abyss. Success is not assured; it must be cultivated (and even then, it’s not assured). Expecting consumers to “get with the graph” is a techno-geek fantasy more entertaining than most VR titles. Which brings us to the issue of VR’s value proposition...

What’s so funny about VR?

It’s currently fashionable for VR content creators to self-deprecatingly observe that “nobody knows anything” when it comes to VR. Baobab Studios seemed intent on proving this at the 2018 Hong Kong FILMART, when they gave a presentation stating (to the astonishment of myself and others) that “You can’t do cuts” in VR and that “Comedy does not work” in VR. These questionable takeaways were all the more baffling given that each has already been disproven.

VR editing...

As early as 2015 (which sounds funny, but is apropos for VR), and contrary to those who maintained that you can’t edit in VR, cinematic VR pioneer Jessica Brillhart was sharing her adventures in “probabilistic experiential editing:” “I realized (VR) was about going from experience to experience instead of going from clip to clip, like a ripple effect - like a drop in a bucket, and then a ring around that, and a ring around that. (Editing in VR) was really about rotating those rings to corral people through the general idea of a story, or an experience. Then I thought, if I know that they are going to be doing certain things, I can edit for that sort of experience. And that got me to “probabilistic experiential editing.” Central to the concept of “probabilistic experiential editing” is another concept: “points of interest,” or simply: places in a scene where a viewer is likely to be looking.”

In short, it’s simply not true that you can’t edit in VR. But it is true that you can’t complacently apply conventional editing paradigms to VR. When someone says, “You can’t do this,” what they are actually saying is “WE haven’t figured out how to do this”.

VR comedy...

The forehead-slapping conclusion that “comedy does not work in VR” stems from an observation that the tradition of comedy in films is not empathetic (i.e. - comedy results at the expense of another) and VR is an “empathy machine.” Therefore, “comedy does not work in VR.” Let’s unpack this.

First of all, and with all due respect to Chris Milk, entirely too much is being made of VR as an “empathy machine.” Though it’s unsurprising that folks will jump on the bandwagon of a viral TED talk, VR is not inherently empathetic any more than life is inherently empathetic. Few are compelled to see the zombies’ point of view in The Brookhaven Experiment. VR can facilitate empathy, superiority, revulsion, lust, anger, amusement, etc... and none to the exclusion of the others.

Secondly, it is entirely incorrect to conclude that the tradition of comedy in film excludes empathy. Certain comic forms may appear to sublimate empathy, but when we seem to be laughing at the expense of another, we are truly laughing in recognition of ourselves. One needs look no further than Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights for evidence of this. Conversely, people used to say that animation was only suitable for comedy until Walt Disney brought audiences to tears with Snow White.

Anyone struggling to wrap their head around VR as a comic form should experience Miyubi, the immersive short film by Felix & Paul. Miyubi features a comic premise that puts you in the position of a Japanese toy robot given to a boy as a gift. From your absurdly low point of view, you observe the controlled chaos of a suburban family, while struggling with your own technical issues. It’s familiar, fantastic and funny all at once.

“Funny is money,” as the saying goes. If VR creators can’t get their heads around immersive media as a comic form, then mass-market adoption will remain a pipe dream. We can’t afford to be knuckle-headed about this (unless in the spirit of The Three Stooges).

Red flags

The myopia infecting the VR ecosystem is insidious, non-trivial and exacerbates the disturbing lack of consumer traction. VR hardware manufacturers are struggling, VR content creators are scrambling, and VR users are neglecting their headsets. VR is a frog that no amount of wishful thinking will turn into a prince, but that hasn’t stopped the wishes from flying.

I’ve previously commented on the hopes that many in the VR industry have (mis)placed on Steven Spielberg’s film adaptation of Ernest Cline’s dystopian novel Ready Player One. The technorati envisioned RPO as a game-changer which would entice the uncon(VR)ted into an immersive embrace (rather like hoping for a boost in beach tourism following the premiere of Jaws). I subsequently posited four (mutually non-exclusive) potential reactions to the Ready Player One movie with respect to the VR ecosystem:

- Indifference.

- Niche enthusiasm among first adopters and gamers (who are already invested in VR tech, so no gain).

- A rush of interest in VR experiences among audiences, followed by a crush of disappointment in the state of those experiences.

- A Luddite backlash against VR by those who fear the dystopian consequences of technological escapism as depicted in the film.

The apparent outcome: 1 and 2.

VR evangelists love Spielberg’s Ready Player One (even as they snicker over his misunderstanding of how VR actually works), while general audiences have collectively given the film a “B.” In short, no VR “bump”.

So, now what?

A few weeks ago, I had lunch in Beijing with a traditional media producer who now works on VR projects. Over bowls of dan dan noodles, he shared what he’s learned so far - not about the details of VR technology and VR content, but about what he sees his employers (and their audiences) needing (and wanting) with respect to VR.

He bluntly noted that his employers aren’t looking for so-called “VR experts,” and are wary of those who present themselves as such. As always, his employers are looking for experienced producers, directors, art directors, managers, animators, etc... who are experienced and adaptable - people who can come in, get the lay of the land, and deliver the work.

He then commented on the fallacy of VR “creating more pie” for “new audiences.” There are no new audiences - there are only the existing audiences. VR technology will (if all goes well) be tied to the content that those audiences already consume. VR shorts will be tied to the short film market (a path to trophies, but not to riches). VR series and features will be tied to the broadcast and theatrical markets (pending practical distribution and viewer adoption). VR experiences will be tied to the location-based entertainment market (with perhaps the most promising near-term revenue model).

Bottom line: you can’t force, cajole or wish audiences into VR. “How does VR become a truly mainstream technology?” It can only do so by applying to how people live, work and entertain themselves.

In short, VR must...

...offer a compelling value proposition to the average person.

...displace existing technology (replacing TVs and phones).

...be cheap and easy.

Let’s shake off the evangelical myopia and address those points with eyes wide open, if only to ensure that chart waving isn’t the sole form of comedy associated with VR.