Two-time Daytime Emmy Award-winning writer/director Eric Darnell talks about Baobab Studios’ Annie Award-winning immersive VR experience and the sometimes confusing world of virtual reality.

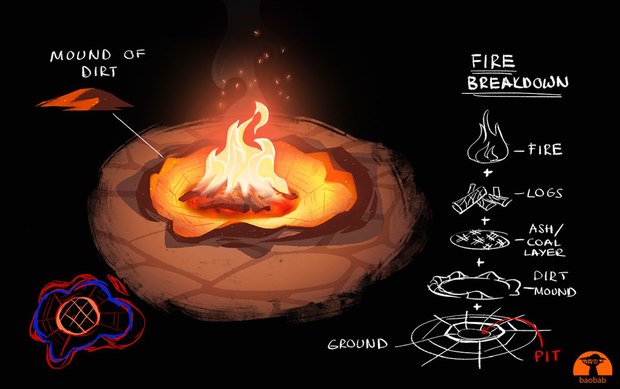

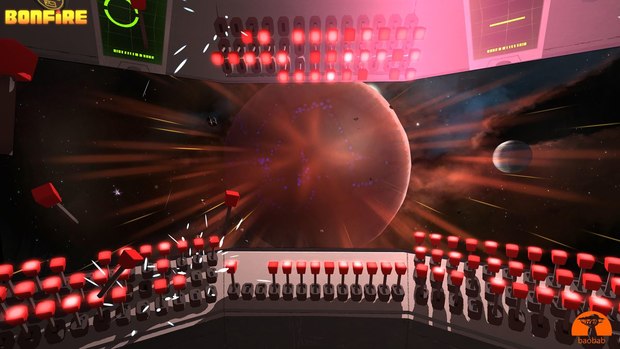

So, say you’re a space scout entrusted with the mission of finding a new home for the human race, but, being a mediocre pilot at best, you crash-land on a mysterious planet 300 light years from Earth, where your only source of light is a makeshift bonfire, and your only companion is a neurotic robot. Such is the premise of Baobab Studios’ narrative-based, animated, immersive VR experience, Bonfire, a comedic first-person adventure that premiered at the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival and just won an Annie Award this past Saturday night for Best Virtual Reality Production. (Bonfire’s acclaimed predecessor Crow: The Legend received the first-ever Annie Award bestowed in this category.)

Featuring the voice talent of actress and comedian Ali Wong, Bonfire, like Crow: The Legend, was written and directed by Baobab co-founder and two-time Daytime Emmy Award-winning chief creative officer Eric Darnell, otherwise known as the director of four Madagascar films and Antz. We sat down with Eric at the 2019 VIEW Conference in Turin, Italy, to talk about the production of Bonfire and related topics, including, to begin with, exactly what this thing they’re creating should be called.

AWN: It seems as though every day there's a new vocabulary to talk about the area in which you work: experiential, immersive entertainment, experiential entertainment, interactive storytelling, VR… It’s a medium that involves narrative storytelling, it's virtual reality, it's 360 environments, it's a lot of things. When you talk about your projects, what do you call them?

Eric Darnell: I don't think we really have a great name for them, and it’s a little frustrating. Terms like “experience” sound vague or perhaps even New Agey. So, I don't know. Theatrical films were called “moving pictures” in the beginning, which effectively described what they were, but it didn't stay the term. It got shortened to

“movies.” I was talking with Kevin Kelly of Wired and he proposed that we call them

“realies.” There're movies and then there's realies. I don't know who's going to be the evangelist to make something like that stick, but it's probably not me. Some people have suggested “VREs,” but everything just feels somehow not quite right or cumbersome or too vague. I think we need to come up with something that's short and catchy and probably doesn't mean anything literally.

The other thing that makes it difficult is that there is a big difference between, for example, virtual reality games and virtual reality documentary work, where you're not a character, you're a fly on the wall. Between virtual reality that is pre-rendered and interactive virtual reality that's not games strictly, but it's more storytelling. A term like “virtual reality” covers so many things, including stuff that's not entertainment – healthcare, tourism, manufacturing, training, real estate, and all the potential ways that people can use VR now and in the future. So that’s a long-winded way of saying I don't know.

AWN: Well, then I don't feel so bad about my own ignorance. My desire is not necessarily to coin something, I just want to make sure that when I talk about these things, I'm referring to them properly so that I can communicate properly.

Darnell: Yeah. What do you call the person who's in the VR headset? Are they the player? Are they the viewer? Even that becomes sort of difficult. I could see saying “the VR viewer” if it's a canned piece of VR, but if you're interacting, yet it's not a game, what are you? Are you a player? Are you an actor? It's tough.

AWN: The work that you do also becomes available in the 2D, non-VR world, so to speak. When you're approaching projects, at what point do you think about how they would be in 2D, or how they would be if someone wanted to turn them into a series or a film? Is that something that you're always thinking about?

Darnell: Unless there’s a mandate that a particular project must be released as a 2D piece and a VR piece, we don’t think about that when we set out. For me, it’s just a matter of trying to come up with the best story, trying to come up with great characters that people are going to want to engage with and they're going to care about. Then somebody says, I really like that, I like that story, I like that world, I like those characters. How can I spend more time with them? The answer may be another piece of VR, maybe a book, a film, a TV show. Some of the things that we do might translate more easily to another medium than others. I know that [CEO and co-founder] Maureen [Fan] would love it if everything we did could immediately be plugged into any other form of presentation. But if we're doing the VR piece first, then it's just got to be a great VR piece, even if maybe it's not one that's going to be ideal for another medium.

AWN: In each of your projects – INVASION!, ASTEROIDS!, Crow: The Legend, Bonfire –you built on your previous work, expanding on it, experimenting, innovating in new areas. Where do you go next? What are some things that are important for you to accomplish to help with your business?

Darnell: I really think that the discoveries we made leading up to Bonfire, and what we've done in Bonfire, do all build on each other, as you say. So, I think for me the next thing is to take what we've learned and do it even better. That means having better stories, having better characters obviously. I think it also means creating seamless ways for the viewer to be integrated into the story and the experience that allows them to feel like they have as much freedom as they would want to have.

There's a lot of tension between giving the viewer all the freedom to do what they want, go where they want, and also having a great story and telling it well. The extremes of that are, like, you just walk around and find stuff and whatever, versus you're on a rail and there's nothing you can do to get off that rail. I think that the advantage of the rail is that you can really define that story and you can have a lot of control over it. The disadvantage, of course, is that the viewer may feel trapped. They can only do certain things at certain times and that breaks immersion and it starts to show the hand of the creator.

So, the challenge is to do everything we can to resolve the tension between the viewer feeling completely there and immersed and able to do whatever pops into their head, and telling that great story and telling it well. I have ideas about how we can do that. I think a lot of it is about finding more opportunities to allow the viewer to grow during the experience. So, more opportunities to make choices and make decisions that cement a relationship with a character in a way that actually feels truly meaningful. To have worlds where you feel like you have the freedom to do whatever you want to do. If I can pick up that cup or that bottle on the table and that's what's important for the story, but I can't pick up that other thing because that's not important for the story, that's seeing the hand of the creator.

Giving viewers the experience that here's this world and go ahead and do with it what you will because it's all there for you. That's a super-huge challenge. It means that viewers may stray wildly from where you'd like them to be going. A big part of the director’s job is to inspire the viewer to make the completely “free” choice to do what you want them to do, when you want them to do it. They don't feel like they're being pushed. They don't feel the hand of the creator, but they want to do the thing that you want them to do.

I believe we can do that by creating meaningful, believable relationships with characters and worlds, so that viewers feel like, "Yeah, I get it. If I pick up a flaming log and throw it at a character, they're going to run away. If I pick up a piece of food and throw it at it, they're going to come closer." Those kinds of things. The challenge is that introduces a great deal of complexity, and that requires all the things you'd imagine, like money and time and all the things that you don't have unlimited amounts of.

AWN: Apropos of which, what are the biggest creative and technical challenges in what you're doing?

Darnell: Well, you've only got so much processing power. So, you have to acknowledge that limitation and then do everything you can inside it. A lot of my career has been about defining the box and then getting inside of it and taking advantage of what's there. I don't mind that. I think we all have to do that, especially in the world of cinema, where we're depending on teams of people and things can get expensive quickly. It's the challenge of creating with limited resources and a small pipe and reaching as many people as you can. Also, creating an experience where people feel like they're there, where nothing will prevent them from suspending their disbelief. You make compromises, like simplifying your characters, simplifying your worlds, finding natural ways to limit what a viewer can do that don't feel contrived. There are a lot of limitations and the only real solution is to just embrace them.