Cartoon Saloon’s Jeremy Purcell and Guru Studio’s Sanatan Suryavanshi & Sheldon Lisoy detail the complex compositing process behind the meticulously designed story-within-a-story sequences of the Oscar-nominated animated feature.

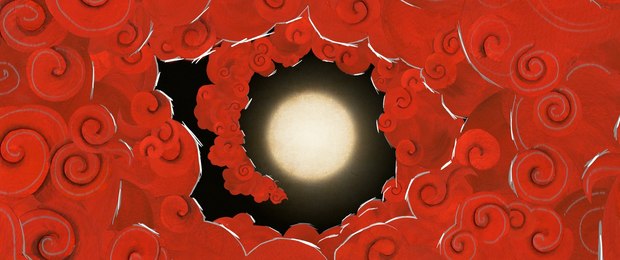

‘Goat Woman’ Story World sequence from Academy Award-nominated feature ‘The Breadwinner.’ Images © 2017 Aircraft Pictures/Cartoon Saloon/Melusine Productions.

The Breadwinner, a meticulously crafted story of self-empowerment and imagination in the face of oppression, showcases the breathtaking hand-drawn animation that has made Cartoon Saloon one of the world’s most beloved and respected animation studios. Nominated for an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, the Ireland-Canada-Luxembourg co-production follows Parvana (voiced by Sarah Chowdry), a young girl living under the Taliban regime who disguises herself as a boy in order to provide for her family after her father is imprisoned.

Led by Nora Twomey in her first solo directorial outing, Cartoon Saloon brings Parvana’s story to the screen with gorgeous imagery that pays homage to the beauty of Afghanistan as it was in 2001, when the events of the story take place. The color palette is inspired by the “Honey Light” of the Middle East, employing delicate, muted pastel tones that contrast with the pop of red of Parvana’s headscarf.

Led by Nora Twomey in her first solo directorial outing, Cartoon Saloon brings Parvana’s story to the screen with gorgeous imagery that pays homage to the beauty of Afghanistan as it was in 2001, when the events of the story take place. The color palette is inspired by the “Honey Light” of the Middle East, employing delicate, muted pastel tones that contrast with the pop of red of Parvana’s headscarf.

Juxtaposed with Parvana’s real-world life in Kabul are the wildly fantastical cut-paper “Story World” sequences, depicting mythic tales in lush environments that are free of physics dominated by jewel-toned reds and greens and black. Comprising nearly 15 minutes of the finished film, including the title sequence, the Story World sequences appear to be animated using stop-motion paper cutouts, but in reality were achieved entirely using digital animation.

“We're not a paper cutout stop-motion studio, so early on we made the decision not to go down that route,” explains The Breadwinner’s Story World sequence director Jeremy Purcell, who previously served as visual effects supervisor on Cartoon Saloon’s The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea, as well as assistant director on both seasons of the studio’s preschool series Puffin Rock. “Other people who are dedicated towards that are really good at it, and we felt it would be an injustice for us to do that, or that we would just have to hire in a studio to do it,” he says.

“We're not a paper cutout stop-motion studio, so early on we made the decision not to go down that route,” explains The Breadwinner’s Story World sequence director Jeremy Purcell, who previously served as visual effects supervisor on Cartoon Saloon’s The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea, as well as assistant director on both seasons of the studio’s preschool series Puffin Rock. “Other people who are dedicated towards that are really good at it, and we felt it would be an injustice for us to do that, or that we would just have to hire in a studio to do it,” he says.

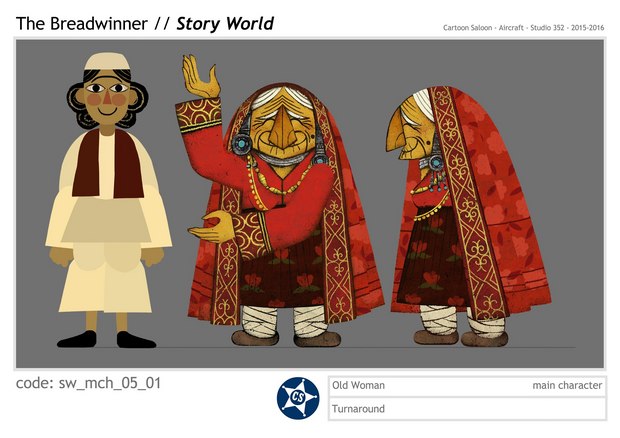

Starting with early character designs developed by Reza Riahi and rendered in paper by Janis Aussel, Purcell and his team began a series of live-action tests with cameras and lights, working in the basement of the studio because it was the darkest room available. “We looked a lot at those tests, and not only for the amount of light flickering or how shadows were working, but also how intricate a design could be, because Janis could only cut so small,” he recalls. “That really informed the size of the trees in the background and a lot of other details like that.”

Following these initial tests, Cartoon Saloon teamed with Canada’s Guru Studio to help complete the Story World sequences, bringing the Toronto-based studio on to composite into backgrounds what was initially conceived as relatively simple layers of 2D imagery in order to create a stop-motion effect. But that soon changed once the team of artists at Guru -- led by art director Sanatan Suryavanshi and compositing supervisor Sheldon Lisoy -- began to experiment with the layers, adding paper textures and lighting to create more depth and drama.

“We really wanted to explore the idea of narrative lighting and see how this could be used to enrich the paper cut-out sequences,” Suryavanshi says of the early development process. “Story World needed to be quite a bit different from the real world of the film, and we started experimenting with light and color to see how we could push a sense of magic and wonder. We also started experimenting with depth, which is something Nora came up with very early on. She wanted Parvana’s storytelling to evolve as the film progressed, and we had to find a way to visualize that evolution in terms of light, color and the size of the digital-paper sets,” he recounts.

“We really wanted to explore the idea of narrative lighting and see how this could be used to enrich the paper cut-out sequences,” Suryavanshi says of the early development process. “Story World needed to be quite a bit different from the real world of the film, and we started experimenting with light and color to see how we could push a sense of magic and wonder. We also started experimenting with depth, which is something Nora came up with very early on. She wanted Parvana’s storytelling to evolve as the film progressed, and we had to find a way to visualize that evolution in terms of light, color and the size of the digital-paper sets,” he recounts.

“Our approach was to identify and replicate specific qualities that made something read like paper -- the edge catching light, texture from the tooth, and specularity, and then carefully design the light in every sequence so that it would pull all the elements together into seeming like paper while also servicing the story ,” Suryavanshi continues, noting that he worked closely with Twomey and Purcell to design the light and color for Story World and much of that seen in the final frame was generated by the team at Guru. “Ultimately we were all hoping to create a unique aesthetic that also felt like actual paper had been photographed.”

The end result is comprised of thousands of layers, carefully textured and lit and then composited together to form the final scene. To create each shot, Cartoon Saloon animated the characters on rigs within Smith Micro’s Moho Pro (formerly known as Anime Studio Pro), placing individual body parts in what quickly added up to hundreds of separate layers. Also using Moho, Cartoon Saloon worked with backgrounds that had been flattened out so lighting and camera moves could be determined. These files were then handed off to the compositing team at Guru Studio, which rebuilt them from scratch using Adobe Photoshop for the 2D elements and then carefully stitched them together in Foundry’s Nuke.

“Cartoon Saloon would deliver the file to us, and Chris Fourney, one of our amazing TDs, would strip down the file into the dynamically changing layer order of those characters, and build what we were calling depth maps,” Lisoy details. “Chris would render out the characters for us, sometimes up to 6K or 7K in resolution just to make sure we're getting all the crispness out of the image. And then we would use this depth pass to calculate shadows, and rim light, and occlusion just on that one character. Then the compositing artist would rebuild the entire scene in Nuke using the camera projections and raw Photoshop layers.”

“We separated out every single element of every single background, even body parts of characters,” Lisoy observes. “That allowed us to procedurally shift shadows and drop in occlusions, rim lights, a little specularity here and there,” which in turn allowed Twomey or Purcell to make detailed changes such as shortening shadows or softening edges. “In CG, you tend to hit render 1,000 times to get one good looking image,” he adds. “Whereas we can hit render once and then tweak all of our layers.”This workflow enabled Guru to define even the most minute details within a scene, rebuilding the separated parts of characters with transparency passes to give them dimension and even determine the thickness of the paper.

Many shots were built in 2K resolution, but more complex shots, such as those with giant panning moves that traveled through multiple backgrounds, would go up to 20K. “We were blown away by the power that Nuke gave us to work in those types of resolutions and rebuild these massive scenes all in one file,” says Lisoy. “Using the initial camera file as a reference, “we would render out multilayer EXRs of the hundreds of different background layers as well as character layers, as well as import all of those into a secondary comp-pass file, which we would reassemble with our proprietary lighting system that was connecting all of those layers together and allowing the artist to basically move around one or two light controllers,” he details.

The video below demonstrates a lighting pass completed for “Elephant Mountain,” one of the more complex Story World sequences:

This video shows one of the early tests completed for the sequence:

And this video shows the final sequence as it appears in the film:

This digital workflow also allowed Twomey to direct even the smallest details of each frame while avoiding the costly re-shoots that stop-motion animation would entail. “We had a final stage that we called the quality control stage,” says Purcell. “Before sending a sequence off to Guru, we would do a frame-by-frame quality control check. And even at that stage Nora would be present, and she would ask for small changes to pupils and eye direction and stuff like that, which, because it was digital, we could make the change and re-render it and still meet our shipping delivery that afternoon.”

Each sequence within the Story World presented its own complications. “The sequence with Sulayman running up the hill was very challenging for our background department,” Purcell offers as one example. “It’s a massive background, and the compositing team had to reconstruct it and add all the multi-plane effects and all the lighting in between the layers. But the animation itself was a little bit easier for those scenes. The opening, the initial story, on the other hand, was just a lot of characters on screen, which is harder to animate, but the backgrounds were a little bit easier to handle,” he says.

“The final sequences that we did with the jaguars and the Elephant King were probably the most challenging, especially the final two or three scenes with Suleiman and the Elephant because everything had been building up to this point and it called for a lot of subtle acting,” Purcell continues. “We had many lengthy discussions with Nora about how to handle these scenes. She was heavily involved with the animators with these, and we went through a lot of versions of how Suleiman and the Elephant would interact.”

‘Goat Woman’ Story World sequence from The Breadwinner