Shirogumi VFX supervisor Kiyoko Shibuya helped deliver 620 shots, including the giant beast crushing the heavy cruiser Takao, all on a shoestring budget, in Takashi Yamazaki’s hit sci-fi thriller, nominated for a best VFX Oscar at this year’s Academy Awards.

In forging a strong collaborative partnership with Japanese filmmaker Takashi Yamazaki, Shirogumi VFX supervisor Kiyoko Shibuya was able to successfully lead the delivery of an incredible array of visual effects on Godzilla Minus One, a film made on an incredibly slim budget of $15 million. It’s a testament to their collaboration that the film is competing for a Best Visual Effects Oscar at the 96th Academy Awards against the likes of Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3, which cost $250 million. In this iteration of the famed franchise established by the Toho Company in 1954, a kamikaze pilot fails to kill a mysterious creature at the end of World War II; the consequences of this failure become apparent two years later when American nuclear testing transforms the creature into the iconic kaiju.

“Many fictional characters have appeared in director Yamazaki's previous works, but in this film, in addition to representing Godzilla itself, the phenomenon of the sea and the destruction of the city caused by Godzilla himself were also important elements,” notes Shibuya. “In particular, the ocean was the setting for important scenes from the final stages of the plot, and we had to think about how to simulate the ocean, how to film the small wooden boat carrying the actors and the large destroyer, and how to achieve the shots that the director envisioned within a limited budget.”

As well writing the screenplay and directing, Yamazaki supervised the visual effects work, articulating what he was looking for through storyboards. “Since the director himself draws the storyboards that form the basis of all designs, we have direct access to the shots, angles, and production effects that he envisions,” states Shibuya. “Based on these storyboards, previs was created, and detailed discussions were held for each shot, including the shooting method and location selection. In the process, all staff members shared the finished image and any problems. The Yamazaki team has a long history of working together, and many of the staff members have a long history of working together, so I think one of the best things about this team is that everyone was able to quickly materialize the image envisioned by the director.”

Godzilla is viewed in Japan as both a god and monster, so the physical movements had to have a divine feel to them while the ferocious nature was emphasized by making the dorsal fin more acute and legs thicker. “For Godzilla's animation, we first thoroughly worked on the way he walks,” explains Shibuya. “Godzilla's image changes remarkably with just a slight change in the position of his waist. If his waist is raised, it looks too godlike, and if it is lowered, he looks too much like a monster. I had a hard time deciding on the posture that would give the impression of both god and monster, which was my goal for this project.”

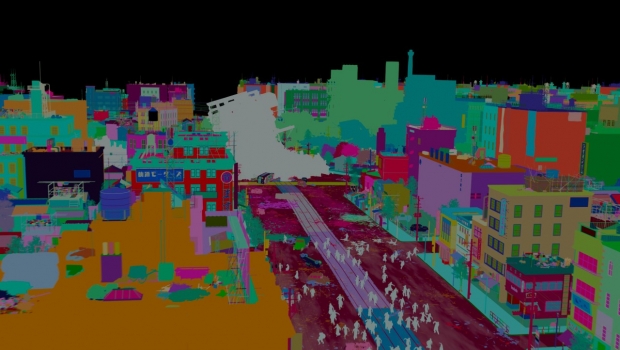

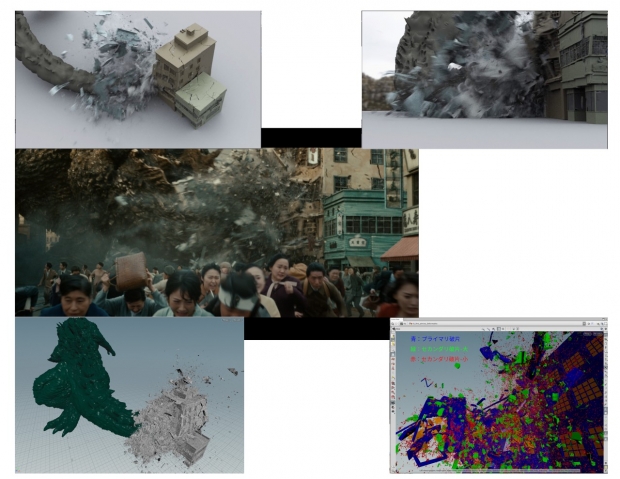

Not only did Godzilla have to be believable, but the surrounding world did as well. “We needed to faithfully recreate the world of 1947 in order for the audience to experience that period realistically and immerse themselves in the story,” remarks Shibuya. “We collected a lot of photos and videos from that time, but Ginza Boulevard was undergoing postwar reconstruction, and the streetscape was changing month by month, so I remember how difficult it was to identify the streetscape we wanted. We could not use an existing open set and did not have the budget to build a new large-scale set, so we asked the art department to create a parking lot with a period-appropriate street surface, a few sidewalks, and storefronts. We did CGI extensions for all other buildings and miscellaneous objects to recreate Ginza's main street.”

In the film, wherever Godzilla goes destruction follows, meaning assets had to be effects friendly. “Since the streets were also buildings to be destroyed by Godzilla, they were created with breakable models that had the texture and thickness of the buildings' materials and the structure of their interior walls,” remarks Shibuya. “Only one staff member was able to devote himself to the destruction sequence, but he used all of his intuition about destruction that he had cultivated over the years to finish the job almost on the first simulation.”

There were 620 visual effects shots created by Shirogumi. One extremely sequence was when the camera circles around Godzilla holding and crushing the heavy cruiser Takao. “While we often see ships exploding or sinking, there have not been many representations of a ship made of steel plates being crushed, and cloth simulation was applied to express the destruction of Takao,” Shibuya reveals. “In addition, we had to incorporate a complex set of effects into the camera work, including the simulation of water generated by the chain of Godzilla's and Takao's movements. The scope and length of the simulation were adjusted by using the camera angles to avoid the need for a huge amount of simulation calculations.

Simulating various types of water proved to be the biggest challenge. “In particular, the shot of Godzilla chasing after the wooden boat was shot with the wooden boat running in the open sea,” remarks Shibuya. “We had to make the CGI Godzilla cover the same waves with the same precision as those generated by the wooden boat. And since Godzilla is much larger than the wooden boat, the waves it generates must also be huge. The most difficult shots in this film were the ones where the live action waves and the huge waves of the same quality were shot together on the same screen.”