VFX supervisor and producer James McQuaide, working with 7 different vendors, delivered nearly 600 visual effects shots, including an incredibly realistic car bomb sequence, in the third film of Antoine Fuqua and Columbia Pictures’ ‘The Equalizer’ franchise.

In Columbia Pictures’ action-thriller, The Equalizer 3, director Antoine Fuqua returns to team up a third time with veteran actor Denzel Washington as a former government assassin, trying to live a quiet life, who can’t help but apply his considerable and unique skills to protect others who are suddenly faced with hostile adversaries they have no possible chance to defeat.

In the film, since giving up his life as a government assassin, Robert McCall (Washington) has struggled to reconcile the horrific things he’s done in the past and finds a strange solace in serving justice on behalf of the oppressed. Finding himself surprisingly at home in Southern Italy, he discovers his new friends are under the control of local crime bosses. As events turn deadly, McCall knows what he must do: become his friends’ protector by taking on the mafia.

Serving as both VFX supervisor and VFX producer on the show was James McQuaide (Candyman, The Lincoln Lawyer, Underworld: Awakening). He was responsible for the production and delivery of nearly 600 VFX shots that covered 60% of the film’s runtime. In addition to his in-house team that handled postvis on the entire film and took some shots to final, McQuaide worked with seven VFX vendors: Blackbird VFX (Sydney); Frame-by-Frame (Rome); Future Associate (Sydney); Luma Pictures (Melbourne); Model Farm (Brisbane); SlateVFX (Sydney); and Supervixen Studios (Sydney).

One of the most “explosive” action sequences in the film involved an incredibly realistic car bomb. According to McQuaide, “The plan coming out of prep was to shoot the Car Bomb sequence at the Palazzo dei Congressi in Rome, relying almost exclusively on the practical, like stunt doubles reacting to a practical exploding vehicle. VFX was expected to handle only basic tasks like rig removals and element augmentation such as smoke, debris, etc. However, shooting of this sequence came late in the production schedule, and at that point, we’d already spent some production time in Naples (which is where this sequence takes place in the movie) and the rationalist architecture of Congressi no longer felt like the Naples we now knew a lot more intimately. From the initial scouts, it had been director Antoine Fuqua’s ambition to shoot the sequence in the Piazza Trieste e Trento in Naples. However, given how continuously congested with people and vehicles the piazza was, this proved logistically impossible. Now with it clear that Congressi wasn’t correct, Trieste e Trento was put back on the table with the idea that VFX would make this ambition possible. This decision came roughly two weeks before the sequence was to be shot.”

In the scene, a CIA operative, played by Dakota Fanning, exits a building, and walks toward her vehicle, which explodes before she reaches it, sending her flying backwards violently. “On the Cinecittà Studios backlot in Rome, there is a standing Old Rome set which includes a large arched entryway whose scale is similar to that of the hero building in Trieste e Trento,” McQuaide explains. “The thought was to use this architecture as a visual anchor for both camera and, more importantly, the actors. We received permission to shoot on the backlot but with the condition that we NOT blow up the vehicle there - the risk of damaging the historic set was simply too great. This decision was made roughly one week before the sequence was to be shot.”

“Now with the production parameters established, Rome-based Frame-by-Frame was enlisted to quickly create techvis based on Antoine and DP Robert Richardson’s storyboards, which was completed just two days before the shoot,” he continues. “The resulting plan called for Main Unit to rig 360° of greenscreen, minus the Old Rome archway, and then shoot the scene save the section in which the vehicle explodes. The vehicle that was to explode was placed within this greenscreen circle only to provide blocking orientation for both the actors and cameras. Camera data and LiDAR scans were carefully taken. In a subsequence shoot, the 2nd Unit photographed the exploding vehicle element on a farm outside Rome – having the hero vehicle as reference in the Main Unit plates ensured the accuracy of the line-up - and the bluescreen element of Dakota’s stunt double flying backwards.”

With production wrapping the day before Christmas, the production secured permission for a crew of six to return to Naples to shoot background plates in Piazza Trieste e Trento, though they had to wait until the holiday decorations were taken down to do so. This allowed editor Conrad Buff time to put the scene together. “In the key shot leading up to the explosion, the camera pans 180° following Dakota’s character as she crosses the piazza towards the exploding car,” McQuaide reveals. “That we weren’t permitted to lock down the piazza was used to our advantage. The documentary-style backgrounds that we would shoot would be populated with real people and vehicles on a normal workday in Naples. The challenge was how to capture this reality in a plate that could cover the 180° pan with sufficient resolution.”

McQuaide met the challenge by deploying the Achtel camera. “Shooting 9K on a HAL 220 fisheye lens, allowed for 190°+ field-of-view in a single plate, which meant we could avoid having to stitch together multiple plates from a camera array, an approach that would have been very compromised by the people and vehicles moving freely thru the background,” he notes. “Back in Naples, applying measurements taken from the Old Rome set entryway to the similar entryway in Trieste e Trento, the Achtel was positioned to shoot BGs that matched the camera positions of the Main Unit plates. The camera’s inventor, Pawel Achtel, operated the camera remotely from his home in Tasmania.”

“In post, the fisheye distortion was removed, providing the VistaVision-like practical BG plate needed to support the 180° pan,” he adds. “Fortunately, for all the shots, or sections of shots where the car actually explodes, the camera is stationary. This allowed for the primary use of the practical elements that had been photographed by the 2nd Unit. However, Frame-by-Frame, who had been awarded this sequence in the wake of their work on the techvis, still had to remove stunt rigs, add additional smoke and embers, bounce and damage CG vehicles, replace the face of the stunt double, etc. to complete the sequence’s more than 70 seconds of screentime. Every audience I’ve seen the movie with jumps when the explosion occurs. That they do so, that there isn’t anything visual that tips off the surprise, is a testament to how photoreal Frame-by-Frame’s work is and the importance of the contribution made by everyone on the team.”

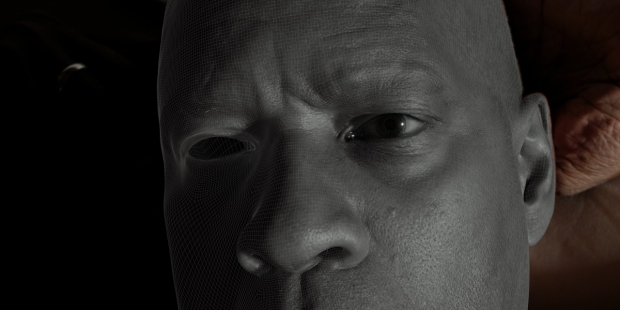

Expanding upon a visual “device” used to great effect in the original Equalizer movie, the production developed what was referred to as “McCall Vision,” where a tight closeup of Washington’s eye reflections shows the audience in advance his plan for a series of deadly moves that will happen in mere seconds.

“In the original storyboards for the opening sequence, McCall sits calmly in a winery basement surrounded by mafioso,” McQuaide describes. “As the camera pushes into a tight closeup of his eye, we see reflected on his pupil how he brutally killed several guards to reach the basement. This flashback material was the first sequence we shot; it was followed directly by the shooting of the scene of McCall in the basement.”

Towards the end of the production, it was decided to further evolve this flashback technique, not just to convey information but to underscore the emotions of McCall calling into question his life and the man he’d become, a central theme of the film. “A new scene was shot of McCall lying in bed, looking up at the ceiling,” McQuaide says. “This scene was to replace the storyboarded basement beat. A loose closeup of McCall was photographed by Robert Richardson. A subsequent scan of McCall was done and delivered to Luma Pictures. Precise matching of textures and lighting allowed for the transition into a fully CG McCall, which proved challenging given that the CG 3D camera had to move not only to the plane of the iris but all the way through the pupil and, metaphorically, into McCall’s mind’s eye.”

Working with the first-person-perspective plates that had been shot as part of the initial week’s production work, Sydney-based Supervixen added McCall’s CG hand, weapons, blood, etc., along with an overall treatment of the image to emphasize it as stream-of-consciousness. “The idea that McCall would shoot a henchman against a mirror that would then, as the henchman slid from frame, leave him confronted by his fractured, bloody reflection was contained in the original storyboards,” McQuaide shares. “However, this idea hadn’t been shot. Given the thematic importance of this new scene, the idea was revived using a stolen plate of McCall aiming his gun at camera along with various CG elements, including the mirror and the room it reflected. The result is an image that symbolically expresses McCall’s state of mind, an image that he then reacts to when his eyes shift from the ceiling to the distant sea in the all-practical shot that follows.”

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.