Winnie Cheung’s fascinating hybrid short film documentary is based on 50 people’s answers to an entertaining but disturbing riddle solved asking only ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ questions.

When was the last time you happened upon an animated short film described with a riddle like this?

A man gets off a boat. He walks into a restaurant and orders albatross soup. He takes one sip... pulls out a gun, and shoots himself to death. So...why did he kill himself?

So, with that as a brief but beguiling introduction, we dig into Winnie Cheung’s fascinating short, Albatross Soup, an animated hybrid documentary based on a fascinating riddle a friend of hers came back with after interviewing for his doctoral program in neuroscience and metacognition at UCLA.

Over 50 people were recorded trying to solve this riddle using only “yes” or “no” questions. Albatross Soup is a visual representation of the riddle unraveling as we hear a rapid-fire kaleidoscopic soundscape of questions from each participant. An all-knowing God-like voice guides the story by answering “yes” or “no” for each question.

According to Cheung, a Hong Kong born, Queens raised filmmaker and editor, “Thought experiments like Albatross Soup are hybrids between puzzles and storytelling. I knew instantly that this stream of consciousness guessing would be the perfect premise for an animated short.”

Upon hearing of her friend’s experience, she was instantly hooked. “The riddle was wild and infectious from the start,” she shares. “You’d want to play it with other friends as soon as you solved it yourself. We played it at bars, house parties and road trips. I had so much fun watching my friends trying to figure it out that I decided to record them and use it as the backbone for an animated short. It made the whole process a lot more fun and intimate.”

Upon hearing of her friend’s experience, she was instantly hooked. “The riddle was wild and infectious from the start,” she shares. “You’d want to play it with other friends as soon as you solved it yourself. We played it at bars, house parties and road trips. I had so much fun watching my friends trying to figure it out that I decided to record them and use it as the backbone for an animated short. It made the whole process a lot more fun and intimate.”

One intriguing aspect of the project was how people projected their own personal narratives on to the riddle’s protagonist. “I had a friend who was going through a rough breakup, so he continually harked on the wife and kept revisiting the marital problem storyline,” she explains. “I knew that I would go to very dark and strange places with this riddle if I kept recording them with my friends, and that’s exactly what happened.”

“We recorded these riddle sessions in groups of 4-6 people,” she continues. “I knew that I had the right friends to come up with funny responses but wanted more textures in the voices to fill out the rest of the film. I enlisted my friend Alex Young, who is now a podcast producer for The Daily at The NY Times, to cast and record sessions with a more diverse group of people. She found a group of kids who had the best reactions. I love how the voices and personalities bump up against one another in the film.”

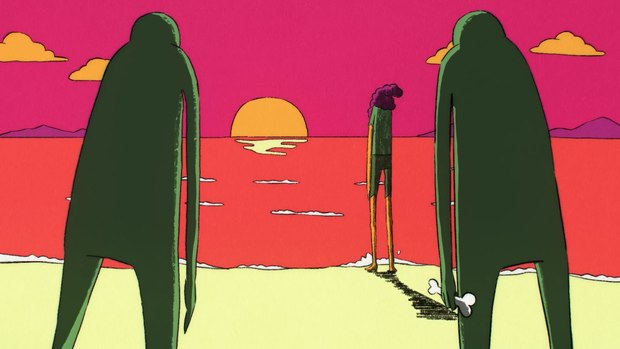

Though Cheung had never directed animation before, she had a distinct vision early on for the film’s look development and ultimate animation style. She enlisted the collaboration of cartoonist and illustrator Fiona Smyth as well as art director and animator Masayoshi Nakamura, to bring her vision to life. “I knew I wanted a visual style that was dark, dreamy and would reflect the brain’s problem-solving process,” she notes. “Fiona and Masa were the perfect match. I loved Fiona’s creepy illustrations and Masa’s fluid animations pushed the non sequitur quality of the riddle. I was already such a big fan of their aesthetic, and I trusted them to do their jobs. I just made sure that our choices were in service to the characters and the story.”

The director’s initial production efforts centered first around music and sound design. “Since I had edited, but never directed, animation before Albatross Soup, I used techniques that I was already familiar with. As an editor, I first put together a radio cut. Then I ‘enlisted’ my husband to create music and sound design. We worked together to flesh out the sonic world even before the visuals came together. When I presented the project to Fiona, she already had a sense of where I was trying to go.”

The film’s visual design changed considerably over the course of the production. “I pulled a lot of references from other animations and graphic novels,” Cheung describes. “These were all meant as conversation starters, but our look and process unraveled along with the story. We started off with a limited color palette and simple shapes but began to add in more details once we learned more about the man and his plight.”

Cheung employed a traditional documentary approach to the editing process, starting with transcriptions of every riddle session recording. “We pulled lines based on themes, characters and plot,” she adds. “We started with a paper script and worked our way up to an assembly. I put together a boardmatic with Fiona’s illustrations and pitched it to Masa, our art director. Since Masa and I had already worked together previously at Cause + Effect Films, I think he had faith in me to get the project done.”

Animation was a true collaboration between the creative leads. “We actually went back and forth between animation and sound quite a bit,” she says. “I felt that my job was to facilitate communication between all the collaborators rather than dictating a look for everyone to execute. Each frame of the final film was hand-drawn by Masa from one of Fiona’s illustrations, and took about three years to complete from beginning to end.”

One of the film’s biggest challenges was navigating the random structure inherent in such a large number of narratives, where each participant’s thoughts drive where the man goes in the story. “It was initially difficult for me to come up with the structure,” she concedes. “At first, I tried to edit it all myself, but half a year into the process, I knew that I had to bring in another editor to move forward. I asked my friend Tessa Greenberg, a talented comedic director and editor, to come on board for some outside perspective. We were able to bring it to a fine cut within a few weeks.”

However, as independent short films have little financial upside potential, financing the film was Cheung’s greatest challenge. “There is very little financial support for indie animation projects in the U.S.,” she shares. “I noticed that when we started touring with the film, we screened alongside a lot of European productions that had so many financier logos at the end of their credits! Since my background wasn’t even in animation, I figured that it was easier and faster to finance it myself rather than applying to an institution that did not yet understand my aesthetic. To be fair, I didn’t know my aesthetic either. As a commercial editor, I can afford to allocate my earnings onto passion projects like this one. Since working on this project, I’ve learned that indie animation is truly a labor of love, but I think the market is changing and I hope that there would be more opportunities to fund and produce animated films in the future.”

For the director, her hope is that people who watch her film come away with a better understanding of how to embrace topics that are often unpleasant and difficult to approach. “When you get to the very end of my film, it’s very unsettling,” she concludes. “The resolution is satisfying for you, the audience, but a complete tragedy for the protagonist. The film is aware of this disconnect, but hopes having a sense of humor brings brevity and empathy to dark and difficult topics that we often avoid in real life.”

For the director, her hope is that people who watch her film come away with a better understanding of how to embrace topics that are often unpleasant and difficult to approach. “When you get to the very end of my film, it’s very unsettling,” she concludes. “The resolution is satisfying for you, the audience, but a complete tragedy for the protagonist. The film is aware of this disconnect, but hopes having a sense of humor brings brevity and empathy to dark and difficult topics that we often avoid in real life.”

Read more about the film, a Vimeo Staff Pick, in the Vimeo Blog, as well as the Albatross Soup website.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.