The famed animator, who brought to life iconic animated characters - villains and heroes - like Gaston, Jafar, Scar, Hercules, and Lilo, talks about his time at the studio as well as the challenge of directing his first film, a beautifully hand-drawn short that tells of a young girl who must save the tiger she has raised from a cub.

For Disney Legend Andreas Deja, it was always going to be animation. At the age of 10, after seeing The Jungle Book, he applied for a job at the studio. Let’s get to it. Though they turned him down, they encouraged him to keep working hard at pursuing his dream. And that dogged pursuit led to art school in Germany, and at age 23, an internship job working with Eric Larson at Disney feature animation. And the rest, they say, is history.

His storied, 30-year career at Disney included work as a lead animator under Richard Williams on the groundbreaking, multiple Oscar-winning Who Framed Roger Rabbit; he also applied his ample talents to some of the studio’s greatest villains and heroes: Jafar from Aladdin; Gaston from Beauty and the Beast; Scar from The Lion King; the titular character from Hercules; and Lilo from Lilo & Stitch.

He animated Mama Odie from The Princess and the Frog and Tigger from Winnie the Pooh. Please… you had me at “T-I-double Guh-Er!”

He was honored by ASIFA-Hollywood with the Winsor McKay Award in 2007. He was named a Disney Legend in 2015. He’s been quite busy.

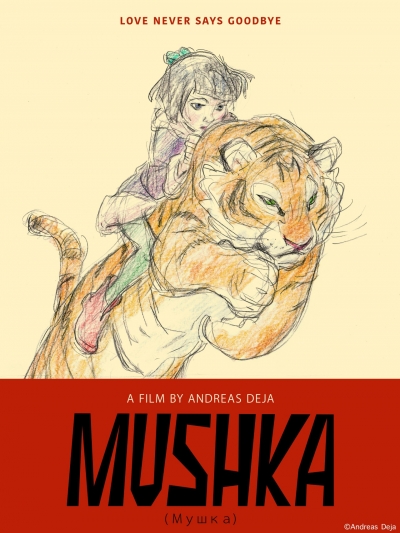

And over the last 10 years, he developed, co-wrote, directed, animated, and produced his own hand-drawn animated short film, Mushka, the emotional and exciting story of a young girl named Sarah and her unlikely friendship with a tiger cub.

I recently had a chance to speak to Deja about his incredible career at Disney, how it feels to look back on having had a hand in creating some of animation’s greatest characters, and how his artistic journeys led him to produce his beautifully hand-crafted 2D short about a father, a daughter, and the tiger she’s determined to protect.

Enjoy the trailer before reading on:

Dan Sarto: You’ve created some of Disney’s most memorable animated characters: Gaston, Jafar, Scar... I remember talking to Glen Keane when he described the magic of bringing Ariel to life for the first time as he sat at his animation desk, flipping back and forth through his pencil drawings. What's it like to bring such an iconic character to life for the first time? To be the one who did it? I know it's easy to look back on such successes after the fact. When you’re working on a film, you have no idea whether it will succeed, or whether or not a character will resonate with audiences. I know that no one who worked on these films ever assumed anything.

Andreas Deja: Exactly.

DS: But looking back on the experience of being part of something that did go on to be so incredibly important and meaningful to people, to fans of filmmaking and animation, what was it like?

AD: Well, I really started with something that, in the end, didn't find an audience, which was the infamous The Black Cauldron (1985). Looking back, the inexperience shows in that film on all levels. Whether it's animation, directing, storytelling, or art direction, it's flawed. It's just flawed. Here we were, most of the kids coming from Cal Arts. I came from art school in Germany. And we were asked to continue on this thing called Disney animation. The old guys had just left, and of course, you can see the inexperience. It wasn't really working yet.

I worked briefly on Oliver & Company (1988), did some character designs and a handful of animated scenes. And then the opportunity came up to work with Richard Williams in London on Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). So, it was really going from one extreme to the other, looking back now, because that one certainly found an audience. It was groundbreaking. It was breathtaking. It was just a high-energy project. We knew we were doing something different over there in London, especially once we saw our pencil tests being sent to ILM, and they did all the compositing, the shadows, the color, all of that. Once we saw how well our animated characters were put into that live-action world, it was just breathtaking. We just couldn't believe what we saw. We knew it was going to be good, but that good for the whole film?

I worked briefly on Oliver & Company (1988), did some character designs and a handful of animated scenes. And then the opportunity came up to work with Richard Williams in London on Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). So, it was really going from one extreme to the other, looking back now, because that one certainly found an audience. It was groundbreaking. It was breathtaking. It was just a high-energy project. We knew we were doing something different over there in London, especially once we saw our pencil tests being sent to ILM, and they did all the compositing, the shadows, the color, all of that. Once we saw how well our animated characters were put into that live-action world, it was just breathtaking. We just couldn't believe what we saw. We knew it was going to be good, but that good for the whole film?

And it was because Dick Williams was just a stickler for perfection. It has to look right. It has to feel right. So, all these technical difficulties of when Roger is grabbing a live-action prop, be sure that that's locked on his hand. If you just mess up two frames and the hand slides up and down on a real glass of water, you ruin the illusion. So, we had to be absolutely perfect on that, and that's what he demanded, and that's what he got.

So, I'm just thinking about the contrast between The Black Cauldron and something that was so embraced by the whole world, like Roger Rabbit, and people still talk about that. I go on YouTube and watch kids' reactions to seeing Roger Rabbit for the first time. And even now, with all the technology, these 16- and 17-year-old kids are still like, “How did they do that?” It's still impressive after all these years. So that was my first entry into being celebrated at the box office, because the first film I worked on didn't have that.

Then, of course, right after that was The Little Mermaid and all the others, each doing more box office than the previous one, and we didn't know where this was all going. Of course, it all really ended up with The Lion King being the top film.

DS: Disney is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. What are some of the things you look back on during your time with the studio that bring a smile to your face? The litany of achievements is staggering. But what do you look back on and say, “I really enjoyed…”

DS: Disney is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. What are some of the things you look back on during your time with the studio that bring a smile to your face? The litany of achievements is staggering. But what do you look back on and say, “I really enjoyed…”

AD: In looking back, I think how lucky I was to have options. The studio did not say, “Hey, Andreas, you're going to animate this character, and so-and-so is going to be doing that character.” That did sometimes happen. And I wholeheartedly agreed. When they offered me Jafar, of course I couldn't turn that down. But then there were other times when, talking about Hercules, where they asked me again to do the villain: Hades. And at that time, early on, they had Jack Nicholson as the voice. He had come in, and I had done a pencil test with Jack Nicholson's voice from a live-action movie to show him what he would look like as Hades. And then that whole thing didn't work out in the end.

But still, they did ask me to continue on with villains. We had a conversation, and I said, “If I keep doing villains, I might run into the danger of repeating myself,” having just done three in a row. I said, “If I have a choice, I would rather do a different character concept. I think I would be better suited doing Hercules because that's a character that's so different than a villain, this sort of guy who is shy around girls and wants to be... He's insecure. He wants to be a hero more than anything. It would give me a chance to shift gears.” So, I was able to shift gears quite a few times. For Hercules, for Lilo, and then for Mama Odie, a funny character. I'm really grateful that I had a chance to jump around and not do just characters that they wanted me to do because they thought that would make sense for the studio. That was really fun, to be able to do different character concepts throughout my time there.

DS: Talk for a moment about Lilo & Stitch (2002). I remember when I came out of the screening thinking, “This is the most non-Disney film I've ever seen.” It's still one of my favorite animated films. When that film was being made, was there a sense that you’d caught a little bit of lightning in a bottle, that this is really a fantastic film?

AD: Yeah. And the people who were heading up the movie, the producer [Clark Spencer], directors Chris [Sanders] and Dean [Deblois], they were a little bit afraid of showing the movie in progress to the management in Burbank because they thought they wouldn't understand this new approach, that we were taking sort of a left turn, that this was not a fairytale. This is a film whose story is unknown. You're asking the audience to go for the ride, not having any idea where this is going to end. Maybe the studio will ask for too many changes and not understand the concept. So, they ended up hardly ever showing this movie as a work in progress. There was one. They really shielded the film. It was also done in Orlando, Florida, away from Burbank. And I remember them saying, “We're going to shield this and keep this as something special so it can't be messed with.” And it really had that feeling that we were off on our own doing our own thing, and hopefully, they will like it in the end. And, luckily, that's what happened.

But it was a special film. For me, Lilo was a character I had asked for because, again, she was for me a different kind of assignment than what I had done before. I had this little misconception because her design was so cartoony. She's almost a mix of a Muppet character and Charlie Brown's “Peanuts,” with the roundness of the head and the big mouth shapes. And I thought... the look ties in a little bit with the 1940s Disney, the roundness of the drawing, the dimensional drawing, not the flatness of the 1960s and '70s. And I thought, “So we're going to do some Freddy Moore animation that's going to be bouncy and fluid.” And it didn't call for that at all.

I mean, Lilo is such an internalized character with all these issues she had. There was a profound sadness within her because her parents had died in a car accident. And now Nani is trying to be not only her sister but also her mother, and that's not going very well. And she also doesn't have any friends at school. So, there are a lot of things that this kid is processing.

But these are real things. Kids like that. Issues that exist in the real world. So, this whole movie was always this crazy combination of a science fiction film with a monster from outer space and a real broken family drama.

DS: Let's now talk about your new short film, Mushka. How did this come about? What's the genesis of the story?

AD: Well, after 30 years at Disney, I thought, “I want to continue on with hand-drawn animation.” I had to. It's in my DNA. I'm not going to leave it behind. It’s for other people, I thought, to do the CG work. I still wanted to explore myself with drawing and art. And after a while, I realized I just needed a project to sink my teeth into. And I said to myself, “Answer a few questions. First, what do you like to draw most?” Animals. When Disney sent me that letter when I was a kid and said, “Go to the zoo and sketch the animals,” I started doing that as a teenager and still love it to this day. So, it had to have an animal in it. What would be a really wonderful animal to animate that I haven't done yet? Well, a tiger is a magnificent animal. I have some experience with big cats from The Lion King, so maybe I can transfer that into this movie and build on it.

And then, in terms of other characters, how about a relationship with a little girl and a tiger? There could be a lot of tension. When people think about that kind of a combo, like a dangerous animal with an innocent girl, it could be interesting to see how that would work. So, I thought, “What if she finds this tiger as a cub, and she raises him, and by the time he's almost grown up, there's trouble because she hears there are some bad people around who want to shoot the tiger and sell the body for profit?” So, the only thing she can think of to save him is to take him to the forest where she found him as a cub, and hopefully, he'll become a wild tiger far away from humans. But things probably don't go according to plan.

So, as an animator, that's all I had. That's not a story. That's just a very rough idea. But I was at least smart enough to ask for help, rather than messing around, not being able to construct a full storyline by myself. I talked to a friend of mine, Michael McKinney, who has never worked for a studio but is one of those freewheeling artists who writes poetry, novels, music. He does people's homes. He designs things. I mean, anything artistic, he does. And I said, "Michael, I really like the way you think.” So, I told him the basic idea and said, “Maybe you could flesh that out for me. Do something that might be a screenplay or a more cohesive storyline.”

He came up with this outline. He brought in a grandmother who was raising this girl because she has a father, who she's never met, who was working in the mines in Siberia. But the grandmother becomes ill, so the girl is sent to live with her father. There's that tension. The two meet and don't like each other. And then, of course, by the end of the movie, they do. So, it's not just about a tiger and a girl. It's just as much about a father and daughter. It really felt like a novel when I read his screenplay, but I liked it for that reason. It felt different. It's not high on laughs and comedy, but it's definitely high on feelings and emotions. Which I liked, so I committed. I said, “I just like it because it has a different tone. Let's just do this.”

DS: What did the early development look like?

AD: Of course, I was itchy and anxious to draw something and not just work with the writer. So, I did some very loose character doodles to sort of set the age for the girl, and to set the design for the tiger. How much realism? What’s that going to look like? Because it was very clear that this tiger would not talk, it would have to be animated almost like a real tiger, but still communicate something that's going on in the head of a wild animal. I knew that would be a fascinating challenge because the other big cats like Scar, of course, talk and have a lot of human qualities.

I started doing some drawings. My friend Michael worked on the screenplay. Then another friend of mine, Matthieu [Saghezchi], came in and helped me with storyboarding. It all happened simultaneously. So that was the process. But I didn't animate until we had the animatic, or the story reel, like we called it at Disney, more or less complete. You can run into the mistake of animating something that isn't solid and might have to be cut, and that's painful, and expensive. I learned that from Disney. So, let's get the story to a point where we are happy with it.

And I remember the first sequence I animated, because I thought, “We might still polish a few things here and there. I like the overall arc where this is going, but there's one sequence that's going to be the same, and that's the Richard Sherman piece.” There's a singing voice in it actually. Our singer is just humming, “Hm, hm, da, da, da, da.” And during that sequence, we see the girl and the tiger bonding. It starts with the tiger as a cub, and by the end of the sequence, he's an adult tiger. So, I had storyboarded that, and said, “Whatever happens around it that we might change a little bit, this sequence will be in it as is." And that was the first one I animated.

DS: How much did the final visual style of the film differ from your earliest designs?

AD: From the beginning, I was set on using a style that would represent an animated sketch versus an animated finished painting, where everything looks very clean and fully rendered. I wanted to go in the opposite direction than I had done with beautiful films like Aladdin or The Lion King, and certainly CG, which is so perfect. I wanted to do something imperfect. So, I said, “Let's sketch our characters. Let's not clean them up with a cleanup crew. Let's have the animators' drawings on the screen,” which is nothing groundbreaking because they did that on 101 Dalmatians, on The Aristocats, The Sword in the Stone, Robin Hood, and The Rescuers. In all of those, many scenes really kept the spontaneity of the animators' drawings without the assistants cleaning them up.

I wanted to do that too, and we did it for the whole film. So, the characters had black pencil outlines, but these are all animators' drawings, not assistant drawings. I also asked that of Natalie [Franscioni-Karp], who painted about 80% of all the backgrounds herself. I said, “Give me something that looks like it's unfinished. Just don't over-render the forest and the train station and grandma's apartment. Just do it like it's a sketch. There's feeling in it and good color, of course, but don't overdo it. Just keep it loose." She got it right away, and it was a nice marriage between our drawings and her background style.

DS: What were some of the roles you took on as director that you hadn’t done during your years at Disney?

AD: It was a little scary at first because, of course, you ask yourself, can you even do it? You have this idea, and you commit to it, but what if you can't do certain things? I just wasn't sure. I had done a little bit of... not directing, but supervising, at Disney. As a supervising animator, you have four or five other animators who also animate the character because you can't do it all yourself. You help them with their work, go over their drawings, make sure the character looks the same. I'd done that. But this was, of course, much more. I had to work with the background painter, Natalie, and two others who helped out, and go over certain areas of the background that should be darker, lighter, or needed a change in color. That was new to me.

And also recording voices, I'd never done that before. That was new. Working with our fabulous composer, Fabrizio Mancinelli, who's Italian, and giving him notes on music, I'd never done that before. But we all agreed to give it our best, and never did it turn into an argument, where somebody said, “No, I don't see it that way.” It was always worked out. When we disagreed even a little bit, we always worked it out.

DS: What skills from your Disney years served you best making this film?

AD: Patience. Just knowing how long animation takes. Each animated film is a journey, and this was no exception. I just didn't know how long it would take to tell this particular story. I was hoping I could do it in 12 minutes, but as we were boarding, timing things out, putting our situations together, and lining them up, it turned out I just couldn't do it in 12 minutes. It was impossible. It really is true that the story took on a life of its own, and it will tell you how long it needs to be told. So, it ended up being 28 minutes long.

DS: What stands out for you about this production? The things you embraced that you thought, “I'm glad I've had this experience.”

AD: A few things to mention. Two important things, actually. I had lunch with Richard Sherman years ago, and I had persuaded him to come to CTNx and play his greatest hits to students from all over the world because they would never have a chance in their life to see him. And he said, “I'll do it.” So, he performed in front of like 2,000 people. But before he went on stage, we had lunch, and he asked me, “What are you doing these days?” I said, “Well, I'm working on a short film.” And I told him about the story. Luckily, that day, I told it particularly well, which I don’t always do. And he got excited, and his fingers were tapping at the side of the table. “Oh, okay,” he said, “maybe somebody at this table here can write some music for your film.” And I was in shock. I thought, “Richard, are you kidding me?” And he wrote this beautiful lullaby that became the central theme for the film. Not just the song at the end; we used it for the score throughout.

The other thing that happened regards my number-two animator, Courtney Dipaola. She had studied animation at NYU and moved to the West Coast just to work on Mushka. And to see her grow and take on really important scenes, there's just a joy in that when you can help nurture somebody like that. That was a highlight for me personally.

And also, just being in charge of the whole thing. Basically, the buck stops with me. Having to make decisions in areas that I wasn't used to working on. At the beginning, that was scary. But it all worked out. We got it finished, and I'm proud of it. When you look back, there are always things that you could polish. That scene… it should be on ones; that strobes a little bit. But it's kind of small stuff. We did get it finished, and in the end, there was no reason to be scared, because I had a small crew that wanted to do the same thing as me: create something great, something as beautiful as it could possibly be.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.