In the third excerpt from chapter one of the book The Advanced Art of Stop-Motion Animation, Ken A. Priebe finishes his history of stop-motion features.

Back in America, 1995 saw a limited theatrical run of Gumby: The Movie, the first feature film starring Art Clokey’s clay icon (Figure 1.29). The story featured Gumby and his pals in a rock band planning a benefit concert, which is threatened by the Blockheads’ attempt to replace them with robots. The feature was actually produced during the wake of the New Adventures of Gumby series, riding the coattails of the show’s newfound success and the fledgling talent who started on the show. Art Clokey financed the $3 million feature himself and stuck with the same level of simplistic charm that had existed in the series. In fact, he simplified it so much that he narrowed his animation team to a third of its original size and took about 30 months to shoot it. The animators who stayed to work on the feature ended up moving on to work on The Nightmare Before Christmas shortly afterward. Production on Gumby: The Movie had wrapped up around 1992, with intention of a fall 1993 release. However, there were significant delays in distribution, and even when the film was distributed, nobody heard about it because there was virtually no advertising or marketing. It was relegated to a director’s cut on video not long after its lackluster release, but it managed to find an audience among die-hard fans of the show.

Clay animation in a feature-length film would finally have its shot at worldwide commercial success by 2000. The 1990s had seen the rise of another stop-motion superstar with the genius of animator/director Nick Park. Park had put the British Aardman Animation, founded by Peter Lord and David Sproxton in the 1970s, on the map with his Oscar-winning short Creature Comforts. This was followed by further Oscar wins for The Wrong Trousers and A Close Shave, starring Wallace and Gromit. Expansion of the latter film to feature-length was pondered at one point, but certain restrictions kept it at the half-hour length of its prequels.

A feature film was the logical next step for Aardman, and several Hollywood studios were knocking their door. The bridge between the two studios would be found in producer Jake Eberts and his affiliation with Pathe Films, which agreed to finance development for a feature. Several ideas based on popular stories were considered, but Aardman felt that an original idea was best. Some drawings of chickens in Nick Park’s sketchbook led to the idea of an escape movie with chickens. Upon pitching this idea to Eberts, the Aardman team found itself in front of Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and David Geffen, founders of the new DreamWorks Animation SKG.

Before long, a co-financing and distribution agreement between DreamWorks and Pathe proclaimed that Aardman’s first feature would be Chicken Run (Figure 1.30), directed by Nick Park and Peter Lord. American screenwriter Karey Kirkpatrick was brought on board to help Park and Lord crystallize their story, which told of a group of British chickens on a farm ruled by the evil Mr. and Mrs. Tweedy. A chicken named Ginger (voiced by Julia Sawalha) dreams of flying to freedom with her friends, who come to believe an American rooster named Rocky (Mel Gibson) is the answer to their prayers. Scenes of mystery, suspense, and adventure ensue as the chickens develop their master plan to escape their fate of being turned into pies by their captors.

The film drew much of its inspiration from the 1963 film The Great Escape and other POW films from the same era, and mixed it with great design, funny characters, and (of course) outstanding animation. Chicken Run was shot in standard 35mm film, but it was the first feature film in Europe to use frame grabbers for digitally storing frames to register the animation. Computer animation was also used for shooting rough animatics of their storyboards to get a better sense of the cutting and motion between scenes. Very little computer animation was used in the film itself, except for a huge gravy explosion near the end. Five years in the making, Chicken Run was a big success for the Aardman/DreamWorks partnership; it became one of the most entertaining films of the year and was loved by audiences and critics alike.

The year 2000 also brought to the screen a stop-motion feature called The Miracle Maker, based on the life of Jesus Christ, a significant story to tell at the dawn of the new millennium. Directed by Derek Hayes, it was a co-production between Wales and Russia, and took 5 years to produce. While the Welsh studio produced some cel animation sequences and overall production, all the puppet animation was developed and shot by Russian animators at Christmas Films, who had a long tradition of adapting biblical stories to stop-motion through their Testament film series.

With Russian animation director Stanislav Sokolov leading the stop-motion production, great attention to detail was paid to capturing the customs, attire, architecture, and landscape of 1st-century Israel with perfect historical accuracy. Puppet animation, which in its very essence is created from scratch with a great sense of purity, lent itself perfectly to taking on this momentous task, and it was taken very seriously by the entire crew. The image of Jesus himself (Figure 1.31) was a culmination of many different representations of him through the ages and was ultimately inspired by photos of people from the region where he had lived. The puppets’ heads were cast in dental acrylic with sculpted replacement mouths and their bodies in a rubber material called Fastflex. The results were stunning in their realism, and were made even more powerful by a moving musical score and unique script that told the story through the eyes of a young girl named Tamar, based on the biblical Jairus’ daughter, who Jesus raised from the dead in the New Testament (Figure 1.32). Although the story of Jesus had been told across centuries through classical art and also on film, it had never been done quite like this. The film received praise from audiences in theater and television screenings worldwide.

The years surrounding the new millennium saw more stop-motion features that were largely unknown and obscure to most of the world, including The Magic Pipe (1998) from Russia and Prop and Berta (2000) from Denmark. In Czechoslovakia, two feature-length anthologies called Jan Werich’s Fimfarum (2002) and Fimfarum 2 (2006) delighted audiences with a menagerie of short stories directed by noted stop-motion filmmakers Aurel Klimt, Vlasta Posposilova, Jan Balej, and Bretislav Pojar. South Africa also produced its first animated stop-motion feature film in 2003, called Legend of the Sky Kingdom. It was based on a children’s book by producer Phil Cunningham, and employed puppets and sets built from found objects of junk (therefore, the film was referred to as “junkmation” by the filmmakers). This was not only a budgetary restriction, but also an homage to the folk art of Africa, which is often made from discarded objects. In 2005, Colargol animator Tadeusz Wilkosz brought a new puppet feature to Polish cinemas called Tajemnica Kwiatu Paproci (The Secret of the Fern Flower), and Kihachiro Kawamoto completed a new feature called Shisha No Sho (The Book of the Dead).

The year 2006 saw completion of the 13-year production of an independent stop-motion feature called Blood Tea and Red String (Figure 1.33), directed by American filmmaker Christiane Cegavske. Cegavske was an art student who was inspired upon seeing Jan Svankmajer’s Alice, and she began animating short films while studying at the San Francisco Art Institute. Her short-film projects began to grow into what would become her feature, which was financed mostly by working as a lead animator and sculptor for various studios in Los Angeles. Blood Tea and Red String, described as “a handmade fairy tale for adults,” tells the story of two groups of creatures, the White Mice and the Creatures Who Dwell Under the Oak, and their conflict over gaining possession of a beautiful doll. The story is filled with surreal, dream-like imagery, is told entirely without dialogue, and features a haunting musical score by Mark Growden. The award-winning film played in several film festivals and was the first of an eventual trilogy by Cegavske, who is now working on her second feature, Seed in the Sand. (Cegavske’s production stills and other artwork can be found at http://www.christianecegavske.com.)

Meanwhile, as independent rarities of puppet features spawned across the globe, Aardman was busy moving forward on its multi-picture deal with DreamWorks. As Chicken Run wrapped, pre-production moved forward on a re-telling of the Aesop fable The Tortoise and the Hare, but story problems prevented the feature from going any further. There had been talk of making a feature-length film with Wallace and Gromit, so it was finally decided to pursue it as the next project, entitled Curse of the Were-Rabbit (Figure 1.34). This time, Nick Park would co-direct with Steve Box, who he had also worked with on the last two Wallace and Gromit short films. The story told of the classic man-and-dog duo and their adventures rescuing their local village from a giant mutant rabbit that threatens to ruin the annual Giant Vegetable Competition.

The filmmaking techniques used for the new film were mostly the same as had been used before, although there were some new uses for computer animation employed for certain effects. CG was used to animate the bunnies floating around in the Bun-Vac 6000 machine used by Wallace and Gromit to capture an entire brood of bunnies; it would have been difficult to animate this in stop-motion. The clay texture of the bunnies was scanned onto the CG models to keep the same appearance, and the effect is seamless. The film also employed some creative use of green-screen compositing and fog effects to aid in creating certain shots for the horror film atmosphere. Overall, the film retained the hand-crafted quality, humor, and classic British flavor of the original short films while becoming more epic in scope to appeal to a mass audience. It is a movie made by and for people who love movies, filled with nods to Metropolis, King Kong, Beauty and the Beast, The Wolfman, An American Werewolf in London, and the Hammer horror films of the 1960s, all put together for a smashing good ride.

While Aardman was producing its feature in Bristol, another stop-motion feature was being produced at Three Mills Studios in London: Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride. The genesis of the film can be attributed to the late Joe Ranft, who was a storyboard supervisor on The Nightmare Before Christmas. Always one to recognize a good story, he came across a European folk tale about a man who unknowingly proposes to a dead woman. He told Tim Burton about the story, knowing it was “something he could really capture,” and before too long Burton’s sketchbook got some ideas brewing. Similar to Nightmare, Burton knew the project called to be done in animation, but he let the project gestate for several years until the time was right to bring it forward. Following Nightmare, of course, there was a glut of CG films straddling the late 1990s and 2000s, including Burton’s own Mars Attacks! (which was CG after being originally meant to feature stop-motion). When Corpse Bride figuratively rose from the grave of his sketchbooks, some thought was given to using CG. A few tests were done, but Burton knew that the project would have much more resonance if it was done in stop-motion.

At first, the film was considered to be produced at the former Will Vinton Studios in Portland, but the partnership was not meant to last. When the project was officially given the green light by Warner Bros., a crew of regular Burton collaborators combined with new talent was assembled in the U.K. Mike Johnson was chosen as co-director. Johnson had been an assistant animator on Nightmare and went on to direct a short film called The Devil Went Down to Georgia and several episodes of The PJs at Will Vinton Studios. The puppets (Figure 1.35) were designed by premier fabricators MacKinnon & Saunders, and were the first to employ a new technique for facial animation. Rather than extensive use of replacement heads, as had been done in other films, the Corpse Bride puppet faces were manipulated by complex mechanisms of paddles and gears underneath a silicone skin. Animators would insert a tiny Allen key into holes positioned in the puppet’s ear or the back of the head to make the jaw drop, the corners of the mouth twitch, and other kinds of subtle movements.

The other breakthrough for Corpse Bride was the first use of digital still cameras for shooting all the animation. This decision was made 2 weeks before production was to start, despite the fact that they had 30 classic Mitchell film cameras and piles of film stock on the shelves ready to be used. The entire film was shot with Canon EOS-1D Mark IIs and provided instant feedback of each scene, which made dailies easy to view and approve on the spot. All of the digital scenes were cut together using Apple’s Final Cut Pro, which was another first for a stop-motion feature.

Corpse Bride opened just 2 weeks after Curse of the Were-Rabbit in October 2005, and both were nominated for Best Animated Feature at the Academy Awards (against Howl’s Moving Castle). The simultaneous mainstream releases and nominations were unprecedented for stop-motion in general. On Oscar night 2006, Wallace and Gromit took home the prize, which was the third time for Nick Park’s beloved dog and his owner, but a historical first for a stop-motion feature film. Despite this success, Aardman parted ways with DreamWorks after completing its third feature, Flushed Away, which was done in computer animation.

Riding on the popular success of these films, Switzerland’s first major foray into stop-motion feature production (with co-production from France, Belgium, and the U.K.) came about with Max & Co. It was the first feature by directors Frederic and Samuel Guillaume, two brothers who had previously made a few short films. The story, incorporating detailed animalistic puppets designed by MacKinnon & Saunders, told of a teenager named Max on a search for his father. He is taken in to work at a fly-swatter factory called Bzzz & Co. and gets involved in a mission to save the local village from the plot of an evil scientist. With a budget of nearly $30 million, Max & Co. was the most expensive film project ever produced in Switzerland. Production set up in an old Tetra Pak factory in the small Swiss town of Romont, with a diverse international crew of stop-motion and live-action filmmakers. The animation director was Guionne Leroy from Belgium, who had experience working on Toy Story, James and the Giant Peach, and Chicken Run. Many of the other experienced stop-motion artists came from England, working with others from Canada and all across Europe (Figures 1.36 and 1.37). The director of photography, Renato Berta from Switzerland, had nearly 30 years of live-action credits to his name and was shooting his first stop-motion feature. Many unique techniques contributed to the dark urban atmosphere the directors were aiming for, including photography of real local skies and landscapes composited into the backgrounds.

Despite critical raves and winning the Audience Award at the 2007 Annecy Animation Festival, the official European release of Max & Co. in February 2008 did not live up to expectations. It only sold 16,000 of the 110,000 tickets anticipated, and the production company formed to create the film declared bankruptcy. This turn of events obviously limited the potential for a wider release, and so far the DVD release has apparently been limited to France. The extremely high production values, fluid animation, sophisticated puppetry, and beautiful design that went into the film make Max & Co. an unfortunately lost gem that may simply slip into cult status.

A similar fate befell the final release of Canada’s first stop-motion feature Edison and Leo (Figure 1.38), which had a smaller production budget of $10 million, funded by Vancouver’s Perfect Circle Productions, Telefilm, and Infinity Features. Written by George Toles, the film was set in the late 19th-century Canadian prairies and centered on the exploits of shady inventor George T. Edison. When a failed experiment injures his wife, Edison’s plea for help to a native tribe results in a series of murderous plot twists, including the electrification of his son, Leo.

The “steampunk” tone of the film was decidedly not geared toward a family audience, and it featured scenes of graphic violence and sexual innuendo. The original director ended up leaving the production midway and was replaced by Neil Burns, who had stop-motion experience from working at Cuppa Coffee Studios in Toronto. Many of the animators also re-located from Cuppa to work on the feature, which was shot in the gymnasium of a former First Nations school in Mission, British Columbia. The location was also home to most of the puppet fabrication, set workshops, and post-production. Scenes were shot with digital still cameras, and the images traveled through a fiber-optic cable network straight to the editing suites in house. (I had the opportunity to visit the set during production and was pleased to find one of my former stop-motion students working in the puppet department.) For a relatively low-budget project, they attempted to put a good level of detail into the look of the film, in particular the beautiful set design. Unfortunately, the dark story and mean spirits of the characters were not enough to endear most audiences to the final product. The film played in the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2008 and the Ottawa Animation Festival in 2009, but it did not secure a standard theatrical release and went straight to DVD. Historically speaking, it is great that Canada has finally produced a fully animated stop-motion feature with a unique visual style, and hopefully it will happen again.

In production at the same time as Edison and Leo was another stop-motion feature with a very adult sensibility, an Israeli/Australian production called $9.99 (Figure 1.39), directed by Tatia Rosenthal. Rosenthal was born in Israel and is now based in New York, where she studied animation at NYU’s Tisch School for the Arts. (The influence of her studies definitely made its way into $9.99; she based the design of one of her puppet characters after the Tisch School’s head of animation, Oscar-winning animator/historian John Canemaker.) Prior to her feature, Rosenthal had made two stop-motion shorts—Crazy Glue and A Buck’s Worth—in collaboration with Israeli writer Etgar Keret. The latter film consisted of a tense dialogue scene between a businessman and a homeless man, which served as the basis for what would become $9.99.

Armed with a low budget, 5 months of pre-production began in Australia in August 2006. Production began in 2007, shooting with digital still cameras and a small crew of animators for 40 weeks, and post-production was completed afterward in Israel. Using naturalistic puppets of humans made from silicone, the feature consists of several interweaving stories surrounding several tenants in a Sydney apartment complex. The thematic elements of the various characters’ encounters are tied through the common thread of 28-year-old David Peck, who is reading through a book claiming to explain “the meaning of life, yours for only $9.99.” The existential script walks a fine line between fantasy and reality, and although it has the feeling of a live-action film, it is presented in a fashion that has much more resonance through being animated.

Rosenthal referred to the style dictated by Keret’s stories as “magical realism,” which lent itself well to the stop-motion medium. Certain elements of the film, like a young boy dreaming up intricate shadow puppets on his bedroom wall and another character portrayed as a winged angel, would have stuck out as effects gimmicks in a live-action film, but through an entirely stop-motion universe, they fit much better, with a style all their own. The puppet characters are realistic in their movements, but stylized enough to present themselves as more impressionistic and symbolic to the philosophical musings of the screenplay. Overall, the film is very unique, bringing a fresh, mature approach to stop-motion among the more caricatured mainstream offerings geared more toward kids. Several noted Australian actors, like Geoffrey Rush, also lent their voice talents to the film. $9.99 premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2008, and the following year began to find its way into theaters and festivals, picking up positive reviews and awards along the way.

Australia was not only home to the production of $9.99, but also Adam Elliot’s feature Mary and Max (Figure 1.40). Elliot was already established as a successful figure in the independent animation scene, with several short films and an Oscar to his credit. While studying animation at the Victoria College of the Arts in 1996, he made a strange 6-minute biographical clay animation short called Uncle, which was a surprise hit at several festivals. Elliot’s signature style brought forth in his film consisted of very limited animation of clay characters, who often stared blankly at the camera, and shooting in black and white. A low, deadpan narration told the story behind the tragic lives of these plasticine characters in a matter that is unsettling yet very touching. The power of Elliot’s films lies in the brilliant writing, combined with funny character design and a blend of humor and melancholy. Uncle was followed by a series of short films executed in the same style of dark, dry wit: one called Cousin, another called Brother, and finally the 22-minute epic Harvie Krumpet, which would take home the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film in 2003.

Riding the wave of this success, Elliot would spend the next 5 years crafting his first feature-length film. Mary and Max is recognizable as the same signature style of his previous films, but it is brought to a whole new level of beauty, storytelling, art, and technique. The story tells of a pen-pal relationship between Mary (voiced by Toni Collette), a young girl living in Australia, and Max (voiced by Philip Seymour Hoffman), an obese Jewish man with Asperger’s syndrome living in New York. They continue writing letters back and forth as Mary grows into adulthood and Max goes through a series of personal trials, ultimately moving toward a beautiful, touching conclusion. Like his earlier shorts, the film is dark, sad, poignant, and hilarious, all at the same time. Elliot drew from many personal experiences writing and directing the film, basing it on a real pen-pal relationship he had and his thematic exploration of people who are different. The film was shot with Stop Motion Pro software interfacing with digital SLR cameras by a talented production crew that included six animators and about 120 other artists and technicians. Hundreds of tiny props, puppets, and sets were hand-crafted for the film, and according to production facts from the U.S. press kit, more than 7,800 muffins were consumed (5,236 by the director). Mary and Max opened the Sundance Film Festival in 2009, which was a first for both Australia and feature animation, and really helped to push the animation medium to a higher level of acceptance by the film industry.

Panique au Village (A Town Called Panic) is yet another stop-motion feature that has recently toured festivals and theaters, premiering at the Cannes Film Festival. Based on the TV series of the same name by Stephane Auber and Vincent Patar in Belgium, the aesthetic of A Town Called Panic (Figure 1.41) deliberately resembles tiny, old-fashioned plastic toys moving crudely and erratically through miniature clay sets, and typically features fast-paced gags and hilarious slapstick. The main characters of the series and the feature are housemates Cowboy, Indian, and Horse. In the feature, Horse falls in love with his music teacher, Madame Longray, and Cowboy and Indian wake up remembering that it is Horse’s birthday. They frantically decide to make him a barbecue as a present, which results in the destruction of their house and a series of adventures involving a giant robotic penguin and a family of underwater sea creatures. The crude nature of A Town Called Panic, developed by the directors when they were art students, is completely at odds with the more carefully crafted films it shares the screen with, but that is half the point. The wacky French dialogue, jittery animation, and lightning-fast pacing of the film and its bizarre story make it a fun ride (and incredibly funny).

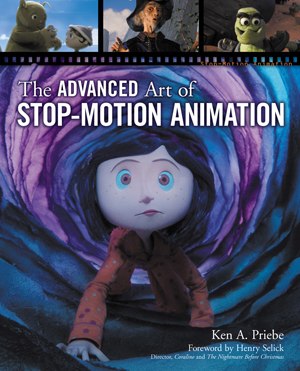

While these independent features were hitting the festival circuit in 2009, the first big stop-motion feature event for mainstream theaters that year was Coraline (Figures 1.42), released in early February. The evolution behind the filmbegan when famed horror/fantasy writer Neil Gaiman fell in love with The Nightmare Before Christmas and was inspired to work someday with director Henry Selick. He wrote Coraline as a novel, inspired by his own daughters, and sent the manuscript to Selick, who also fell in love with the story and wanted to make it into a film. The story was about a young girl named Coraline who discovers an alternate world through a door in her new house. Everything in this “other” world seems to be much more enticing than her life in the real world, but it soon unravels into a nightmare that Coraline must find a way to defeat.

The project went through many years of finding the right studio, distributor, and medium to bring it to the screen. Choices to make it live action, computer animation, stop-motion, or a combination of these finally came to a head in 2006, when production as a fully stop-motion feature finally began at Laika Studios in Portland, Oregon. Laika had been Will Vinton Studios before it was taken over by Phil Knight in 2002. Coraline would be the first feature produced under this new regime. The crew was a unique combination of talent, combining many who had worked consistently with Selick since his MTV days with local Portland artists and others from around the globe.

The film was the first to use two new technologies for stop-motion filmmaking: rapid prototyping and stereoscopic photography. Rapid prototyping was a method for printing out 3D computer models of replacement animation and props into physical resin materials in order to combine the technical smoothness of CG into a stylized stop-motion set. Stereoscopic photography was a method for actually shooting the stop-motion sets in 3D by taking left- and right-eye images of each frame and aligning them for stereo 3D projection. (Both of these techniques are described in more detail in Chapter 3: Building Projects and Chapter 4: Digital Cinematography, respectively.)

Even with this new technology and state-of-the-art compositing effects, every effort was made to keep Coraline as hand-crafted as possible. Amazing miniature work was done in the puppet fabrication department, in the realms of posable hair, tiny knit sweaters, and innovative animated plants for a fantastic garden sequence. Focus Features did an incredible job marketing the film through a creative website and effective advertising, and the anticipation paid off upon the film’s release. Audiences and critics alike gave it glowing reviews, making it a great success. As a whole, the awesome vision of Gaiman and Selick made Coraline a masterpiece that set the bar much higher for what the art of stop-motion could accomplish, in its design, story, animation, and technical innovation.

It is fascinating to note that the nearly 80 years of history behind the theatrical puppet feature began with Starewitch’s Tale of the Fox and has come full circle with Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox (Figure 1.43). Anderson did admit that the Starewitch film inspired the look he wanted for his film. Based on the classic children’s book by Roald Dahl, the film tells the story of Mr. Fox and his attempts to save his family from being captured by his human arch enemies. Anderson took great liberties with expanding the content of the book into enough story material for a feature in his own signature style of deadpan humor, flat compositions, and eccentric characters. The puppets were fabricated by MacKinnon & Saunders, with elaborate facial paddles for very detailed but subtle animation. Also, aesthetically, Anderson wanted to maintain the crawling fur that would occur when the animators touched them.

Several unique approaches were taken to the production itself, done at Three Mills Studios in London. The voices, done by George Clooney, Bill Murray, and other well-known talent, were recorded on location rather than in a studio. This made the characters feel more like they were living in their respective scenes, whether they were in a field or inside a cave. The animation director was former Will Vinton Studios animator/director Mark Gustafson, who coordinated production on the actual sets. Wes Anderson directed the film mostly by e-mail from his office in Paris, viewing and commenting on still pictures and motion tests for his crew members remotely on a regular basis. He wanted as much of the film’s effects as possible to be done in front of the camera, utilizing cotton for smoke and large strips of cellophane for an iconic waterfall scene. The results were a very creative, hilarious film that caught audiences and critics by surprise with rave reviews in late 2009. It has a very adult sensibility in the vein of Anderson’s other films, but is still intelligent and entertaining enough for kids to enjoy. Both Fantastic Mr. Fox and Coraline were nominated for Best Animated Feature at the Academy Awards, a fitting tribute to the long-overdue recognition of the stop-motion feature film and its history.

As 2010 is upon us (at the time of this initial book printing), the future looks bright for feature films made in stop-motion animation. What is also fascinating is just how international the spectrum is for these films. Animaking Studios, the largest animation studio in Brazil, has been working for the past several years on its first stop-motion feature, Worms (Figure 1.44), based on its award-winning short film of the same name. The new feature film is made for all ages, with a focus on children, following the adventures of a pre-teen worm named Junior. The film is slated for release in Brazil and Latin America very soon, and it appears to be receiving much support from distributors, media, and followers of their production blog (http://www.minhocasofilme.com.br).

Elsewhere, a stop-motion feature called O Apostolo is being produced in Spain, a feature version of the TV series Sandmunchenn in Germany, and in Poland a stereoscopic stop-motion feature is being produced called The Flying Piano. Back in the U.S., Screen Novelties is moving forward with the Jim Henson Company on a feature version of their short film Monster Safari (which you can read more about in Chapter 2: Interview with Screen Novelties). There is also an independent feature by Julie Pitts and Miles Glow in Australia called Wombok Forest still in production, and indie stop-motion filmmakers Justin and Shel Rasch (see Chapter 14: Interview with Justin and Shel Rasch) have dreams and plans for a feature project in the years to come.

In addition to independent features, the larger studios are moving forward on more stop-motion feature productions. Aardman Animation is producing Pirates under its new partnership with Sony Imageworks, and Tim Burton has officially joined forces again with Disney to create a feature-length stop-motion version of Frankenweenie, the live-action short he made for Disney back in 1984. Meanwhile, stop-motion fans are waiting with anticipation as plans come together for future projects at Laika Studios and the next venture for Henry Selick. As the future unfolds, we can certainly look forward to the advanced art of stop-motion animation continuing its history on the big screen, with infinite possibilities and new stories to enchant us.

Author’s Note: This history chapter is dedicated to the memory of Art Clokey (Figure 1.45), whose work was the inspiration behind many of these stop-motion features.

![[Figure 1.29] Gumby and Pokey, stars of Gumby: The [Figure 1.29] Gumby and Pokey, stars of Gumby: The](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/featured/45712-advanced-art-stop-motion-animation-history-stop-motion-feature-films-part-3.jpg?itok=TaHuZWzl)

![[Figure 1.30] Promotional still for Chicken Run. (DreamWorks/ Pathe/ Aardman/ The Kobal Collection) [Figure 1.30] Promotional still for Chicken Run. (DreamWorks/ Pathe/ Aardman/ The Kobal Collection)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-30chickenrun.jpg?itok=KrrnDTkj)

![[Figure 1.31] Puppet of Jesus Christ from The Miracle [Figure 1.31] Puppet of Jesus Christ from The Miracle](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-31jesus.jpg?itok=yOUIBDuz)

![[Figure 1.32] A scene from The Miracle Maker. (© 1999 SAF and Christmas Films.) [Figure 1.32] A scene from The Miracle Maker. (© 1999 SAF and Christmas Films.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-32miraclemaker.jpg?itok=MVH2wcVm)

![[Figure 1.33] A scene from Blood Tea and Red String. (© 2006 Christiane Cegavske.) [Figure 1.33] A scene from Blood Tea and Red String. (© 2006 Christiane Cegavske.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-33bloodtea.jpg?itok=zHD8xkK7)

![[Figure 1.34] Production still from Wallace and Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. (DreamWorks/ Aardman/ The Kobal Collection) [Figure 1.34] Production still from Wallace and Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. (DreamWorks/ Aardman/ The Kobal Collection)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-34were-rabbit.jpg?itok=XLXZkZkF)

![[Figure 1.35] Puppets from Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride. [Figure 1.35] Puppets from Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-35corpsebridepuppets.jpg?itok=dFRG8j2_)

![[Figure 1.36] Marjolaine Parot animates on Max & Co. (Photo courtesy Brian Demoskoff/ characters © Max-LeFilm.) [Figure 1.36] Marjolaine Parot animates on Max & Co. (Photo courtesy Brian Demoskoff/ characters © Max-LeFilm.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-36maxco.jpg?itok=x310OB4o)

![[Figure 1.37] Brian Demoskoff animates on Max & Co. (Photo courtesy Brian Demoskoff/characters © Max-LeFilm.) [Figure 1.37] Brian Demoskoff animates on Max & Co. (Photo courtesy Brian Demoskoff/characters © Max-LeFilm.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-37maxco2.jpg?itok=O753X9B7)

![[Figure 1.38] A scene from Edison and Leo. (© Perfect Circle Productions.) [Figure 1.38] A scene from Edison and Leo. (© Perfect Circle Productions.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-38edisonleo.jpg?itok=-5IZrXL-)

![[Figure 1.39] A scene from Tatia Rosenthal’s $9.99. (Courtesy Here Media/Regent Releasing.) [Figure 1.39] A scene from Tatia Rosenthal’s $9.99. (Courtesy Here Media/Regent Releasing.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-39999.jpg?itok=uN2hr9C2)

![[Figure 1.40] A scene from Mary and Max. (© 2009, Adam Elliot Pictures.) [Figure 1.40] A scene from Mary and Max. (© 2009, Adam Elliot Pictures.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-40marymax.jpg?itok=zAg0BWv2)

![[Figure 1.41] A scene from A Town Called Panic. (© 2009, La Parti Productions.) [Figure 1.41] A scene from A Town Called Panic. (© 2009, La Parti Productions.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-41towncalledpanic.jpg?itok=rz2V4yzQ)

![[Figure 1.42] A scene from Coraline. (© Focus Features.) [Figure 1.42] A scene from Coraline. (© Focus Features.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-42coraline.jpg?itok=X_ZY9XyY)

![[Figure 1.43] A scene from Fantastic Mr. Fox. (20th Century Fox Film/ The Kobal Collection) [Figure 1.43] A scene from Fantastic Mr. Fox. (20th Century Fox Film/ The Kobal Collection)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-43fantasticmrfox.jpg?itok=nrJhO2nO)

![[Figure 1.44] Production Still from Worms. (Courtesy of Animaking Studios.) [Figure 1.44] Production Still from Worms. (Courtesy of Animaking Studios.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-44worms.jpg?itok=d04gQH8K)

![[Figure 1.45] Art Clokey (1921–2010) (Courtesy of Premavision Studios.) [Figure 1.45] Art Clokey (1921–2010) (Courtesy of Premavision Studios.)](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/45712-stop-motion-ch1-3-45artclokey.jpg?itok=jXs9CT8o)